In the late 18th century, English philosopher Jeremy Bentham formulated designs for a new social institution: the Panopticon, a prison in which a central observer could oversee all of the inmates within a circular structure.

The observer would be hidden from the overseen, meaning the latter had no idea when they were or weren’t being observed. In the end, it didn’t matter. The prevailing threat of surveillance meant inmates would be forced to conform.

When Bentham dreamed up his idea, the logistical difficulties of creating such an institution meant no true examples of his vision ever came to fruition. Modern technologies, however, have made Bentham’s Panopticon a very real possibility.

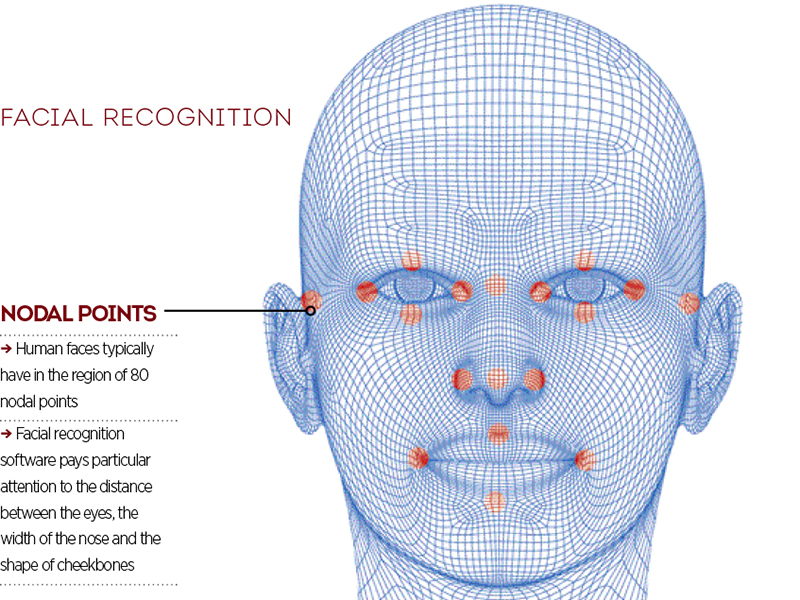

Sensors capable of harvesting your location, monitoring your health and tracking your spending habits are now ubiquitous. Facial recognition software, meanwhile, is being developed to determine everything from your political persuasion to your sexual orientation.

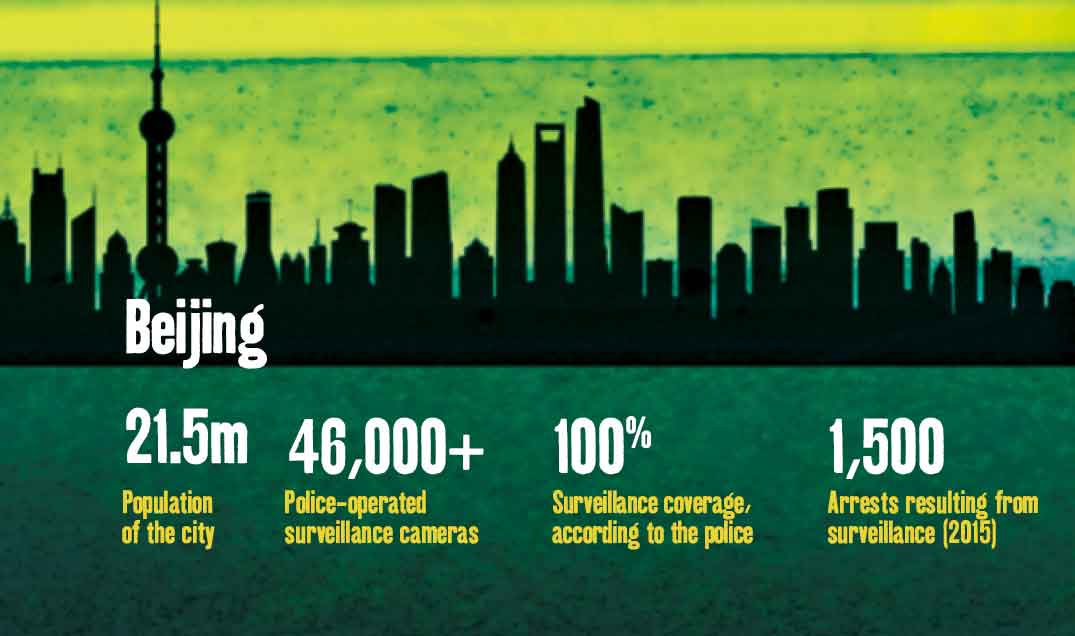

Mass data collection, however, is far from universal. Increasingly, the greatest risk to our personal privacy is taking place in urban areas, where infrastructural, strategic and temporal pressures are driving the need for greater efficiencies.

These so-called ‘smart cities’ are being developed at a rapid pace, with consumers and businesses being lured in by the promise of improved convenience, security and energy consumption. In order to access these advantages, however, the cost to our personal privacy could be huge.

Urban explosion

Smart cities are not gaining support because citizens are eager to have their every action pored over; the main motivation behind urban data collection is necessity. The proportion of the world living in built-up areas is rising rapidly, with 54 percent of the global population currently living in a city.

This proportion is expected to reach 66 percent by 2050. The existing infrastructure simply isn’t capable of managing such an increase, while building new bridges and roads comes with its own associated issues. To cope with mounting urban pressure, cities are refusing to build more, choosing instead to build smarter.

“The benefits of smart cities broadly fit into two categories,” explained Tim Winchcomb, Senior Consultant for Technology Strategy at Cambridge Consultants. “Cities must provide existing services at a lower cost or to a higher standard, while simultaneously introducing completely new services. At times of squeezed public spending, rapid technological developments are satisfying the public’s desire for better information and enabling new city services to emerge.”

A collection of small pieces of data can add up to a surprisingly complete picture of who you are, where you’ve been and what you’ve been doing

One of Europe’s best examples of a smart city is Barcelona, where forward-thinking local governance and the adoption of hi-tech sensors have brought behind-the-scenes efficiencies.

Currently, almost 20,000 smart energy meters help to ensure power isn’t being wasted, more than 1,000 LED streetlights are in place to monitor noise, weather and traffic, and countless ground-based sensors are used to identify the best places to park in the city.

“With so many aspects of our lives becoming smarter, from our homes and offices to our cars, the public expects more information and control than ever before,” Winchcomb told The New Economy. “Smart city services such as information about public transport, congestion or environmental conditions are no different.

As in other aspects of our ‘connected’ lives, we see that individuals are willing to sacrifice small amounts of privacy by sharing their data for increased convenience. The challenge lies in finding the right balance.”

Service or surveillance

For every example of a smart city bringing enhanced efficiency, there is an equally worrying instance of privacy invasion. Even at this early stage, there have been numerous cases of smart sensors harvesting data without consent.

In 2013, retail outlet Nordstrom used smartphone data to monitor customers in 17 stores throughout the US. By tracking Wi-Fi signals, the store was able to measure how long consumers stayed within a particular department. Although only a short-lived trial, customers were understandably concerned when news of the data collection came to light.

Similarly, London-based firm Renew was forced to cancel its marketing programme entirely when it emerged that recycling bins were being used to track the movements of passers-by. In this instance, the collected media access control addresses were anonymised, but the test provided a startling glimpse of the possibilities inherent in smart city infrastructure.

Always in search of the next big thing, major tech firms have begun embracing the burgeoning smart city scene. Technology by artificial intelligence company Emotient that can read ‘micro-expressions’ relating to happiness has already been used to determine what shoppers are thinking when viewing a product or service. Apple purchased the facial recognition start-up in an undisclosed deal in 2016.

Global population living in cities:

54%

2017

66%

2050

It is highly plausible – in fact, probable – that in the not-too-distant future your Bluetooth signal will inform stores of your arrival, a mobile payment device will let producers know how much money you have to spend, and facial recognition software will determine how likely you are to purchase any given item. This isn’t necessarily dangerous, perhaps you don’t even consider it intrusive, but it is certainly unsettling.

To infer is human

Sometimes privacy invasion relates less to the data that is taken and more to what can be inferred from it. It is worth bearing in mind that the only way for smart cities to function effectively is through the mass collection of data. It is not simply a case that smart cities are being implemented poorly; they are invasive by their very nature.

Individually, using your fingerprints to conduct biometric payments in Lille or deciding to scan NFC labels in San Francisco may not appear particularly nefarious. Collectively, however, this data can add up to a surprisingly complete picture of who you are, where you’ve been and what you’ve been doing.

This is why conversations regarding smart city data collection sometimes miss the point. Albert Gidari, Director of Privacy at the Stanford Centre for Internet and Society, believes focusing on personally identifiable information (PII) is myopic – particularly when there is so much valuable data that can be mined from citizens before you’ve asked for their identity directly.

Gidari said: “When the New York Taxi and Limo Commission was forced, under public record laws, to disclose the data collected from cab and Uber drivers in 2016, a data analyst was able to identify specific individuals, their addresses, their employers and their travel habits, even though not a single bit of PII had been collected.”

What’s more, as platforms become more integrated, the threat posed by data inference will increase. “We shouldn’t underestimate the power of adding up lots of small bits of information that by themselves are not particularly sensitive, but in combination may reveal more than we would like,” Winchcomb said. “These could be of commercial value to advertisers or retailers, for example.”

Plans are already afoot to make smart cities more holistic. In Hong Kong, a recently signed partnership between the government and a number of private enterprises is aiming to create a ‘technology ecosystem’.

In Nigeria, meanwhile, the Imperial International Business City is being built from the ground up with data and cloud connectivity at its very core. As smart cities become more established, a comprehensive pattern of a citizen’s life will be worth much more than a disparate collection of datasets.

Nothing to hide

One of the most persistent arguments put forward by proponents of data collection is that privacy concerns are irrelevant unless you have something to hide. On the surface, this has some merit, as the increased threat of surveillance brought about by smart sensors is certainly something that should keep criminals awake at night.

Already, Internet of Things (IoT) devices are being introduced to improve security in urban communities. Flock, for example, is a US-based start-up that describes itself as a “virtual security guard”. It consists of a sensor – paid for by each resident – which records the licence plate of every car that passes by.

When it comes to marketing campaigns, the opportunity to harness personal data may ultimately prove too difficult to turn down

Eventually, facial recognition will be incorporated into the device, but that hasn’t dulled its effectiveness today: evidence collected by the sensor has already been used to convict someone in a court of law.

So far, Flock has been limited to its trial in Atlanta, but support from start-up incubator Y Combinator indicates other neighbourhoods could soon be at risk from similar levels of protection. The company stresses that privacy can be maintained simply by choosing to opt out from the recording process, but that claim does not stand up to much scrutiny.

It is difficult for residents to opt out of something they may not even be aware of. This is why Gidari believes privacy has an inherent value that is worth protecting, regardless of whether it is of criminal interest or not.

“There is a lot about our lives we choose not to share with others,” Gidari said. “Do you want someone to know that you leave the house precisely at eight every day, park in the same spot for work, eat lunch two blocks away at the same place, leave work at five and drive the same route home? All seemingly unimportant points, except it tells others your home is empty for nine hours, where your car is located during that time and whether you should be a higher insurance risk based on your route home. Criminals aren’t the only ones who should value privacy.”

When it comes to marketing campaigns, the opportunity to harness personal data may ultimately prove too difficult to turn down. You may not have anything to hide per se, but you might not want sellers to start targeting you with promotional offers as you walk into a store or pass within 100 yards of a particular brand.

Physical outlets are already at a disadvantage when compared with online portals, which are harvesting data all the time. It may be concerning, but it is hardly surprising if physical infrastructure tries to tip the scales back in its favour. Personal privacy is simply the unlucky fall guy.

A future to fear

If the data being collected by the smart cities of today fills you with dread, then the possibilities posed by future developments do not bear thinking about.

In Chicago, the spectre of predictive policing has already begun to rear its head, with larger datasets leading to the swifter administration of justice. The city’s police force is currently combining crime figures, meteorological data and local business information with broader community statistics to anticipate violent crime. So far, the number of shootings in the city’s seventh district is down 39 percent year-on-year.

These improved crime statistics haven’t gone down well with all parties, however. The American Civil Liberties Union has argued the data being collected is adding bias to the Chicago Police Department’s work.

By contrast, underlying factors such as poor and reduced social mobility are not being addressed. It all sounds worryingly like a Minority Report-style dystopia, but as predictive analytics develops, expect fear of arrest to become a huge driver of improved safety figures.

Cyberattacks also pose a very real threat to future smart city infrastructure. Hackers have already successfully brought down the electricity grid in Kiev and infiltrated a dam in Rye Brook, New York. As valuable data becomes increasingly entwined with city sensors, it too will become a target.

In fact, a chilling vision of the future has already been created as part of an Amsterdam hackathon that took place in 2011. The app Makkie Klauwe – which means ‘easy pickings’ in Dutch slang – used openly available data to determine the best places to conduct crime. Data might prove popular with a city’s police force, but a criminal can put it to equally good use.

“Even if we are happy to share our personal data with a particular organisation, we can’t be sure it won’t be leaked, hacked or simply fall into the hands of someone with bad intentions,” Winchcomb said. “In addition, smart city threats may not become apparent for years to come. The cost of storing data is currently so low it makes sense to hold onto it indefinitely. Even if data cannot be exploited today, there is a chance it may be in the future.”

Data might prove popular with a city’s police force, but a criminal can put it to equally good use

Ultimately, whether or not you feel comfortable with IoT phone booths recording your location or digital changing rooms noting the clothes you wear will likely come down to an issue of trust. As time goes by, more and more connected sensors will begin harvesting your information. Government actors and private corporations may say your data is secure and anonymised, but the question is whether you believe them in a post-Snowden age.

Fight for your rights

If trust isn’t enough, then regulations must be strengthened to protect citizens’ rights. Winchcomb believes international standards are severely lacking and future developments remain untested: “The General Data Protection Regulation, which comes into force in the EU in May 2018, requires organisations to prove that they have consent to hold personal information. This will have an impact on smart city data collection, but it remains to be seen how effective it will be in addressing concerns.”

Investments in data sensors and smart infrastructure are accelerating, and cities cannot afford to fight against the tide. With much of the regulatory change likely to consist of learning as we go, missteps are to be expected, but complicated technology does not always require complicated legislation.

Primarily, transparency needs to improve, with city dwellers often unaware of when data is being collected and by whom. Do app developers, network providers, hardware manufacturers or government agencies possess the data being collected? Or does ownership reside with the individual?

According to Gidari, “data is already part of the mosaic of life”, but data security is not. As open standards proliferate, your car may share data with an environmental agency or your smartphone may provide information to a nearby lamppost. Encryption and malware protection will become increasingly vital to ensure smart city data remains in the hands of the relevant parties.

In the end, we may all find ourselves swept up in the smart city rush. As companies dangle rewards in exchange for data, the loss of privacy could be deemed a price worth paying. Seattle-based company Placed already has an app that will exchange cash or prepaid gift cards for precise location data. The ceding of personal data, however, cannot help but have an impact on human behaviour: for good or bad.

As cities expand, the walls of the Panopticon are drawing in. If the internet is anything to go by, perhaps we don’t mind. Consumers may be more than willing to give up their information in exchange for convenience, efficiency and financial savings. But as the race between technology and urbanisation heats up, it looks like personal privacy is coming dead last.