Online streaming boom signals the end of traditional broadcasting

The popularity of online video streaming services is surging, leaving broadcasters and tech companies scrambling to establish themselves as television’s successor

Netflix first surfaced as a DVD delivery service in 1997, before introducing its on-demand video platform 10 years later. Today, the company operates in 190 countries, with a total 104 million members consuming 125 million hours of content each day

From the way we listen to music and stock our closets to how we purchase everyday goods, it’s safe to say our habits are changing. Perhaps one of the most prominent changes, though, is the way we digest content in what industry gurus are calling the ‘post-TV era’. Traditional television is making way for on-demand streaming, with the former increasingly falling victim to ‘cord cutting’ – the phrase used to define the trend of consumers cancelling their multichannel cable subscriptions in order to fill their couch time with online content instead.

With this change in consumer habits making anyone ill-versed in the latest season of House of Cards feel like an alien, the rewards of producing the next big hit have never been greater. Thus, the entertainment industry has become a battleground: pioneers like Netflix now find themselves crowded by traditional content producers like Time Warner and Disney. Internet giants Amazon and Facebook are also entering the fray, and it seems inevitable that more streaming services are on the way.

This exponential growth can be attributed to a change in the online environment. “The video ecosystem is actively transforming,” said Christopher Vollmer, Global Advisory Leader for Entertainment and Media at PwC. “Pay-TV subscriptions are declining, viewers (other than those older than 65) are watching less linear TV, and younger users are spending a greater share of their time with digital media, including video streaming services.”

History lessons

The rapid surge in online streaming across different formats and connected devices presents a wide range of opportunities for the entertainment industry. In fact, according to Research and Markets, the trend is expected to transform into a $70bn market by 2021, more than doubling the $30.2bn registered in 2016. Recent announcements from the industry’s leading players suggest innovation is the catalyst, with original content currently the weapon of choice for conquering audiences around the world.

Instead of simply acquiring individual shows, Netflix has looked to attract people capable of creating many shows over time

In contrast, the success of video streaming casts doubt over its predecessor’s future: although history shows the radio survived the introduction of cinema and, subsequently, the television, people are less optimistic about the future of traditional television broadcasting. As seen with the demise of Blockbuster, a failure to adapt to the latest technological landscape will likely condemn your company to the annals of history.

The good news, however, is this transformation comes with a variety of financial support and benefits. “There’s a lot of engagement and revenue – from advertising, subscriptions and transactions – associated with video consumption,” Vollmer said. “Consequently, many media – and increasingly, technology – companies are seeing new video content, experiences and services as critical to their overall growth.”

This can be seen most clearly in the transformation of Netflix, which first surfaced as a DVD delivery service in 1997 before introducing its on-demand video platform 10 years later. Today, the company operates in 190 countries, with a total 104 million members consuming 125 million hours of content each day. In the second quarter of 2017, Netflix posted $2.79bn in revenue, beating forecasts to grow 32 percent year-on-year. Analysts now expect the company to outperform the market.

Stealing the show

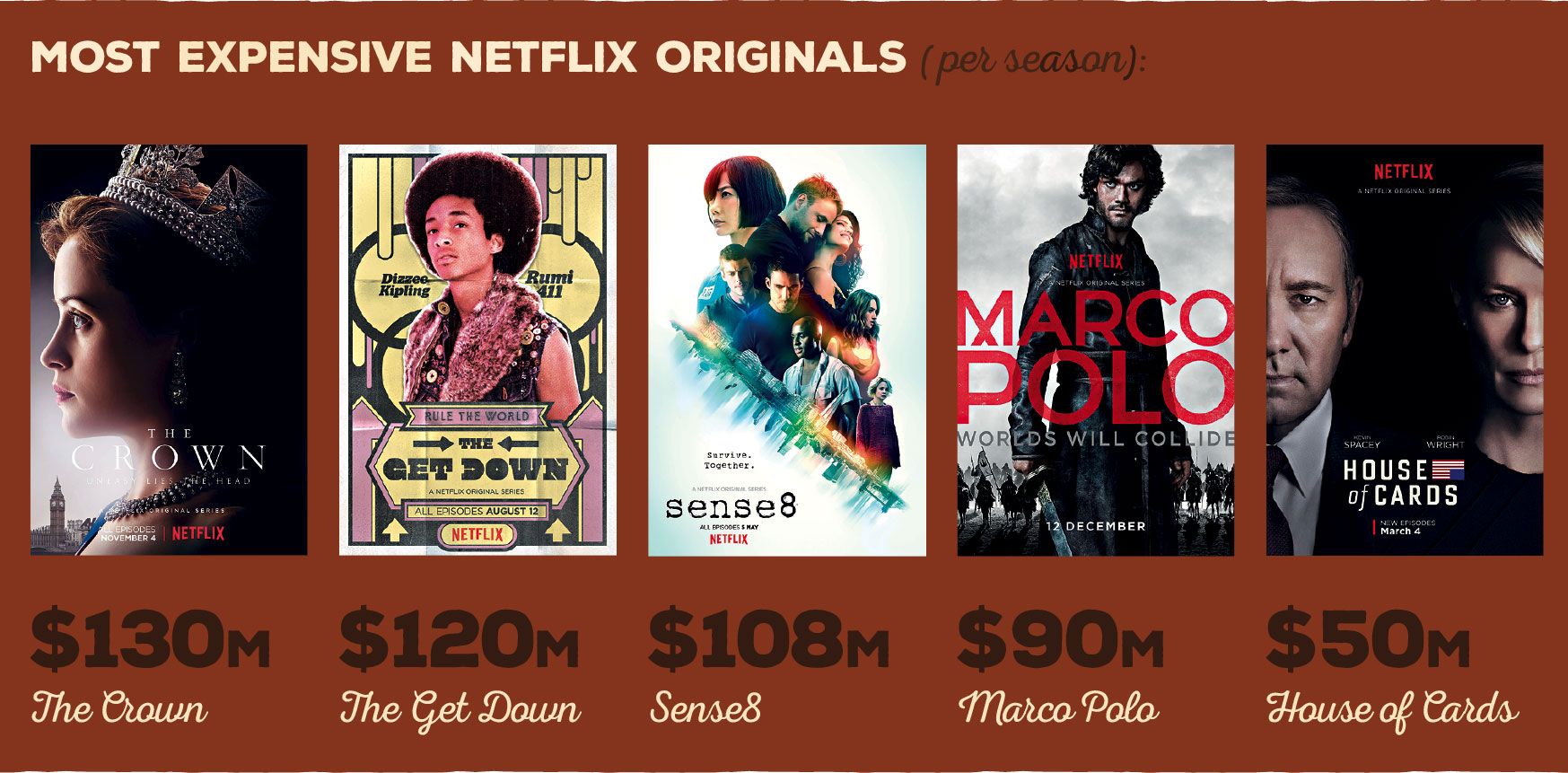

But for Netflix, success has gone beyond numbers: since 2013, Netflix has reduced its reliance on licences by opting to create more original content, differentiating itself from competitors and lowering business risk. This move originally came in the form of award-winning drama House of Cards, which captivated millions before becoming the first online-only television series to receive major award nominations. Later, Netflix would go one further, purchasing the worldwide distribution rights to feature film Beasts of No Nation for $12m.

Advertising spend in the US

$83bn

Digital

$72.7bn

Television

It’s safe to say that Netflix, which is set to spend $6bn this year on both original and third-party content, identified the weakness of being an aggregator early. Indeed, as its success has grown, its relationship with Hollywood has soured. Bert Salke, President of Fox 21 Television Studios, even went as far as to call Netflix “public enemy number one”, after Fox accused Netflix of illegally poaching talent.

As a result, Fox has recently pulled titles such as House MD and The X Files from the platform, while others, like Family Guy, are also set to be axed from Netflix’s roster in the near future. Many of these shows are making their way to Netflix’s competitor Hulu, which is partly owned by the broadcasting giant.

Meanwhile, in August, Disney announced it would also be leaving Netflix, choosing instead to distribute its content via two new streaming services. The first, set to go live next year, will be dedicated to ESPN, while the other, which is scheduled for 2019, will show Disney films and TV shows. Marvel shows will continue to be shown on Netflix, however, as per a separate agreement between the companies.

Staying original

Paul Verna, Senior Analyst at market research firm eMarketer, stressed the importance of carrying an original offer: “Content is the biggest differentiator among the providers. Whether it’s a broadcast network like NBC, a premium cable channel like HBO or a streaming service like Netflix, every content owner is trying to reach essentially the same consumer.

“People no longer differentiate by distribution channel – just by content. In other words, people don’t care if their favourite show is delivered via over-the-air TV, cable or digital. They simply want to watch it.”

While the strength of giants like Disney affords them the opportunity to go it alone, no company racing towards independence is unaware of the dangers of rushing. For those who haven’t built their audiences yet, leaving a platform with millions of subscribers is far from advisable.

For this reason, Vollmer expects the market to combine competition and cooperation. “Near-term, competition will most likely increase as mass market and a growing amount of niche video streaming services battle for user time, attention and spending,” he said. “[However,] the path to profitability can be a multi-year effort, [so] some pockets of ‘coopetition’ are likely to emerge as smaller players partner with larger and more established players for distribution and bundling.”

Meanwhile, Netflix continues to make moves to not only attract users, but also to retain them. Verna highlighted that, instead of simply acquiring individual shows, Netflix has looked to attract people capable of creating a wider range of shows over a longer period of time. For example, in August, Netflix took the unprecedented step of purchasing comic book publisher Millarworld for an undisclosed sum. This was followed by an agreement with Disney’s ABC producer, Shonda Rhimes, who played a significant role in the production of Grey’s Anatomy and Scandal, among other successes.

Although it was a hardware device, the iPhone helped bridge the gap between TV and online content

One distinct advantage of the digital era is that success is not left to chance: like in e-commerce, big data allows content providers to understand what people want. Juan Damia, CEO of Havas Media-owned Data Business Intelligence (Latin America), explained this development: “Machine learning is generating a huge advantage to companies, allowing them to bring their customers more relevant content in real time. In order to generate the right content for the right people in the right moment, companies like Netflix or Amazon integrate, blend, process and generate insights with an acceptable level of certainty for a volume of data that can terrify the most experienced engineer in Silicon Valley.”

For example, Netflix knew House of Cards had the potential to be a huge success before it debuted, with users leaving imprints of interest across its platform. This data, revealed Damia, comes from a wide range of actions and facts, including browsing, scrolling, search, time of day, device and demographics. Everything is condensed to make sure viewers will find something else when they finish devouring a series, film or whatever their preference.

Prime position

Amazon isn’t sitting back either, with Jeff Bezos’ firm having made great strides since first entering the US streaming market in 2011 – a market PwC estimates to be the most valuable of any country, accounting for 47 percent of global internet video revenue in 2016. Last year, the e-commerce titan revealed plans to expand the reach of its Amazon Video service from five countries to 200. Although analysts have attributed the action to a ground plan aimed at increasing the number of Amazon Prime members – who spend almost five times more money than non-members, according to Morgan Stanley – the move has made Amazon one of Netflix’s strongest competitors.

Video streaming market value

$30.2bn

2016

$70bn

2021

In terms of content, Amazon has – until now – taken a different approach to Netflix, investing in original series at a regional rather than global level. Earlier this year, for instance, Amazon reached an agreement with the US’ National Football League, making games available to its subscribers via a deal estimated to be worth $50m. Amazon is also said to be exploring deals with a number of other sports – including basketball, soccer and lacrosse – in order to target fans with its own premium sports package.

Although nothing has been confirmed yet, an offer of this kind would also present an alternative to traditional pay-TV offerings during a time when cable channels are struggling. ESPN, for example, lost 2.9 million subscribers in the year ending May 2016. Netflix has since taken note of Amazon’s move, but reasons for concern keep mounting.

Tech giant Apple is also thought to be developing a new video streaming service, with the Cupertino-based firm first making moves into the TV business when it released the iPhone in 2007. Although it was a hardware device, the iPhone helped bridge the gap between TV and online content.

It is only natural, then, that rumours surrounding an Apple-branded service have been around for almost as long as the market itself. Now, this move finally appears to be imminent, with the iPhone maker recently budgeting for the acquisition and production of video for its platform. In true Apple fashion, the details of such a project remain vague, but sources familiar with the issue have suggested Apple will spend the budget on as many as 10 high-quality TV shows, comparable to HBO smash hit Game of Thrones.

This will build on Apple’s existing offering, which affords customers the opportunity to buy and rent movies via the iTunes Store. Although better known for its vast catalogue of some 40 million songs, the store also has more than 100,000 movies and TV shows ready for download. With Apple seeking to diversify the source of its revenue – which is predominantly generated by the iPhone – this catalogue is likely to increase further, presenting original content as a natural progression.

Consumer is king

As if there weren’t enough players in the video streaming market already, Mark Zuckerberg has announced Facebook is on the path to becoming a ‘video-first’ company. In September, Facebook launched its new service, Watch, in the US, with a view to reaching all two billion of its monthly users in the near future. Offering a range of original short videos (stored as episodes), Watch relies on a number of partners to produce engaging content for its user base.

Share of total viewing hours (online video content):

40%

Netflix

18%

YouTube

14%

Hulu

7%

Amazon Video

21%

Others

In line with the rest of the platform, these videos can then be shared in a personalised social environment, with categories like ‘shows your friends are watching’ encouraging users to engage with new content.

Unlike Netflix and Amazon, however, Watch doesn’t charge its users to access videos. Instead, the content is monetised through advertisements, with users forced to watch pre and mid-roll advertisements in exchange for their content. At a time when Facebook’s News Feed is reaching saturation point, Watch is presenting a new medium for the social network to increase its advertising revenues.

According to eMarketer, digital ad spending in the US surpassed TV ad spending for the first time this year, climbing to $83bn. With the introduction of Watch, Facebook is seemingly hoping to maximise its potential in both markets.

However, Facebook is not the only provider of free content, with YouTube also affording publishers and creators – affectionately known as ‘YouTubers’ – the opportunity to post original videos. Like Watch, these videos are monetised through advertisements, making use of the millions of views YouTubers attract from audiences all over the world. YouTube has also introduced its very own TV service: YouTube TV.

Introduced to the US market in April, YouTube TV presents an alternative to traditional pay-TV services, streaming live TV in return for a $35 monthly membership fee. As the company advertises, YouTube TV is “half the cost of cable with zero commitments”. Accessible from any internet-enabled device, the streaming service provides access to nearly 50 networks, as well as a cloud DVR, where users can store recordings and watch them whenever they want.

In the content era, consumers are increasingly choosing when, where and how they watch content. Although the television still has a special place in living rooms, its popularity is decreasing. According to Frédéric Vaulpre, Vice President of Eurodata TV (Worldwide) at Médiamétrie, daily linear TV viewing is shrinking worldwide, falling to three hours for adults and just two hours for young people.

In contrast, global studies have shown this viewing time is shifting to other platforms. Laptops are currently the most used device for streaming long-form video content, with tablets and smartphones next on the list. With so many alternatives readily available to customers around the world, it seems the question is no longer how long it will take for streaming to overtake television, but rather how long television has left.