“It was nine seventeen in the morning, and the house was heavy.” Thus begins the 2018 novel 1 the Road. Not a bad opening sentence – certainly no worse than many others that have been committed to posterity. The main difference, however, is that this particular sentence has no author – not in the conventional sense of the word, anyway.

This is because 1 the Road was written entirely by artificial intelligence (AI). Its prose was conjured up by a long short-term memory recurrent neural network, which took input – or inspiration, if you prefer – from surveillance cameras and other sensors mounted on a truck travelling from New York to New Orleans. The end result was an AI-penned version of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road.

This new novel is just one example of AI being used for creative endeavours. Those employed in jobs that are deemed ‘low skill’ have long known that automation poses a threat to their livelihood, but musicians, artists and writers have largely assumed that a machine could never replicate their work. Perhaps this confidence was misplaced.

Musicians, artists and writers have largely assumed that a machine could never replicate their work. Perhaps this confidence was misplaced

Not so smart

Every year since 2015, AI has featured as part of Gartner’s top 10 strategic technology trends in one form or another. The technology and the huge impact that it could have on the business world has long been appreciated, but sifting through the hype is difficult. Science fiction has conjured up images of AI that range from benevolent robot housekeepers to apocalyptic supercomputers. Clearly, the technology is not quite at this stage yet.

Nevertheless, AI is no longer something that needs to be discussed in the future tense – it is already here. When customers have an issue with a product or service, their first port of call is often the website of the respective business. Once there, they might join an online chat to help resolve their problem. Increasingly, this dialogue will be between the customer and a chatbot or virtual assistant. They may have a friendly-looking avatar and surprisingly human-like responses, but they are in fact nothing more than multiple lines of code.

In the manufacturing sector, companies like BMW, Airbus and LG are using AI to deliver greater levels of efficiency, safety and reliability on the factory floor. In the home, meanwhile, developments in AI mean that vacuum cleaners can scan rooms for size and obstacles, determine the most efficient cleaning route and then get to work – all without any human input.

These are all impressive feats – ones that would have been scarcely believable just a few decades ago. However, whether they truly represent AI is debatable. In the aforementioned examples, what is termed AI only works within clearly defined parameters: a robot designed to manufacture car parts cannot employ its skills to help put bikes together, and autonomous vacuum cleaners are powerless when confronted by a humble set of stairs.

Artificial general intelligence refers to a machine that can apply knowledge and skills within different contexts – in short, one that can learn by itself and work out problems like a human

“At present, many examples of AI still represent what has been called ‘narrow AI’, working only within clearly defined parameters,” said Arthur I Miller, author of The Artist in the Machine: The World of AI-Powered Creativity. “There is, however, research being done on developing multipurpose machines. DeepMind in London is working on a version of [computer program] AlphaZero, which started out playing games, to work on medical research – specifically, to look into protein folding, the process whereby an embryo begins to generate organs by folding protein chains.”

Self-driving cars, digital personal assistants like Alexa and even automated spam filters fall within what can be termed ‘narrow AI’. Conversely, artificial general intelligence (AGI) refers to a machine that can apply knowledge and skills within different contexts – in short, one that can learn by itself and work out problems like a human. But even as artificial intelligence improves, the number of applications that can be classified as AGI remain few and far between.

Getting creative

One major stumbling block that must be overcome before a machine can claim to possess AGI is the issue of creativity. Humans find it easy to reach beyond the limits of their own knowledge and create something new – it might not be any good (however ‘good’ may be determined), but all of us can write poetry, draw, decorate and cook. These are creative processes, even if we don’t consciously appreciate them as such. Machines, on the other hand, largely do as they’re told.

Increasingly, though, machines are showing their creative side. As well as novels like 1 the Road, an AI bot named Benjamin wrote a short science fiction film called Sunspring in 2016, which was subsequently acted out and played during the SCI-FI-LONDON film festival. It remains available on YouTube.

Journalists, too, have reasons to be concerned. A number of media outlets including Forbes, The Washington Post and Reuters use machine learning tools to help them produce content. Bloomberg uses a computer system known as Cyborg to instantly turn financial reports into mini articles; according to the New York Times, it is now responsible for around a third of all the content produced by Bloomberg News.

Sceptics would say the written word is among the easier creative fields to mimic – after all, it does have clear grammatical rules to follow and there is an almost limitless vault of content for machines to learn from. But AI creativity has extended into other media as well. “Other examples of AI creativity include AlphaGo, an artificial neural network created at DeepMind, which defeated a top-flight Go master in 2016,” Miller told The New Economy. “It did so by making a totally new and unexpected move which went beyond the data on which it was trained – an amazing display of creativity.”

Sony, meanwhile, has used a machine learning platform called Flow Machines to create a song in the style of the Beatles, while in 2019, Warner Music Group signed a deal with an app called Endel for the distribution of 600 algorithm-created tracks to put on streaming services. Similarly, Google’s Deep Dream Generator has been used to create otherworldly pieces of art, some of which have fetched thousands of dollars at auction. The buyers evidently thought the creativity on show was worth paying for.

Machines have even shown an aptitude for thinking on their feet, something previously thought beyond them. Last year, IBM’s Project Debater took on Harish Natarajan, a 2016 World Debating Championship finalist, in a debate over whether preschools should receive government subsidies. Although Natarajan won, IBM’s AI system made a number of convincing arguments, created its own rebuttals to Natarajan’s points and formulated a closing argument.

All work and no play

No discussion of AI would be complete without some consideration of the apocalyptic future that it is destined to bring about – according to some, anyway. Such fears seem hyperbolic at the moment, but that is because there is not much reason to suspect a customer service chatbot is going to take over the world. However, as AI develops further – as it starts to display creativity and emotions – concerns become more justifiable. If AI can do everything better than we can, what is the point of humans even existing?

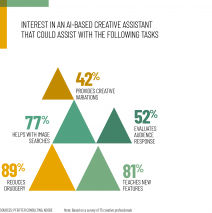

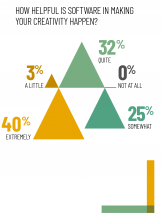

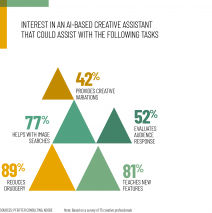

This replacement fear often manifests itself through the prism of job losses. However, Miller believes a creative machine may be able to collaborate with humans more effectively, rather than replace them: “AIs have hugely more information in their memories than humans and can deal with it in ways beyond our powers. They can therefore work with humans to develop new products, which might not be found without their help.”

Still, there is no doubt that creative AI poses a new threat to the workforce. According to a 2018 report by PwC, as many as 30 percent of existing jobs could face automation by the mid-2030s. However, not all industries and job roles would be affected equally.

“Industries follow different paths of automation over time, and data-driven industries… may be most automatable in the short term,” the report read. “In contrast, relatively low automatability sectors such as human health, social work and education have more focus on social skills, empathy and creativity, which are more difficult to directly replace by a machine, even allowing for potential technological advances over the next 10 to 20 years.”

As the ability of AI solutions to work creatively improves, however, even the jobs once considered safe from automation may find themselves at risk. It will likely take a long time before writers, musicians, chefs and artists are replaced, but they should no longer think it impossible. For employers and patrons, the appeal is obvious: AI will never miss a deadline, complain about having to alter its work or ask for more money.

Finding inspiration

The scientific progress that has enabled machines to display elements of human creativity is astounding – so much so that the scientists behind it are themselves not entirely sure what is involved. Developments are generally focused on neural networks – these were involved in the writing of 1 the Road, the development of Google’s AlphaGo, and were used to craft Project Debater’s arguments.

“Artificial neural networks are loosely inspired by the way the brain is wired,” Miller explained. “They are made up of layers of artificial neurons and, like the human brain, require data in order to respond to what they see and hear. They can learn without being specifically programmed to do so. Deep neural networks have many layers of neurons.”

Job automation in numbers:

$15trn

Potential boost to global GDP from AI by 2030

20%

of jobs are at risk of automation by the early 2020s

30%

of jobs are at risk of automation by the mid-2030s

44%

of workers with low education risk automation by the mid-2030s

Source: PwC

Although often compared with one another, the human brain and a traditional computer actually operate in contrasting ways. In a computer, transistors are connected to one another in relatively simple arrangements, or chains. Conversely, in the brain, neurons are interconnected with each other in complex, densely packed layers. This makes computers great for storing huge amounts of information and retrieving it in set, pre-programmed ways. But the brain, while it may take a long time to learn complex information, can reorganise and repurpose it into something new – in other words, it can behave creatively.

In an effort to mimic this creativity, computer scientists have been working on artificial neural networks (ANNs) inspired by the brain. They perform tasks by learning from examples without being given task-specific rules. This approach has shown particular success in pattern recognition, facial recognition, translating between languages and speech recognition.

Importantly, however, there is no physical difference between an ANN and a more traditional computer. Machines built on ANNs still have transistors connected in much the same way as a standard consumer PC, but will be running software that mimics the connections seen in a human brain.

But despite the fact that ANNs are designed by programmers, just like any other piece of computing software, how they work is not always understood. AI suffers from what is known as the ‘black box’ problem: while we have clear visibility of the inputs and outputs of any such system, we cannot see how the algorithms take the former and come up with the latter. How exactly did Google’s AlphaGo platform come up with the playing moves it chose? Why does 1 the Road start the way it does and not with any number of other grammatically correct sentences? We cannot see inside the black box to answer these questions, which means a lot of AI’s achievements stem from guesswork.

Everyone’s a critic

There are many who will say that the examples of creativity that machines have displayed so far are still operating within fixed parameters. When a computer crafts a song, it may be impossible for a human to determine in advance exactly what it will sound like, but there are unlikely to be any other surprises. The machine is only creating music because it has been told to do so – this seems a long way from the spark of inspiration felt by the likes of Mozart or McCartney.

“Machines have shown glimmers of creativity, but we will not be able to say that they are truly creative until they have developed emotions, volition and consciousness and actually desire to create,” Miller said. “They will also need to be able to assess their work. One day, however, machines will certainly be truly creative. There is no reason why only humans can be called creative. Many people who deny that machines will ever be creative do so out of fear of dystopian worlds that are more sci-fi than reality.”

To determine whether machines will ever truly reach this standard, a definition of creativity will need to be agreed upon. This in itself seems like an impossible undertaking. Art is subjective, and whether a machine can be called an artist is likely to remain so as well – at least, until the point when (or if) AI starts to recreate a wider range of human characteristics.

While we have clear visibility of the inputs and outputs of any AI system, we cannot see how the algorithms take the former and come up with the latter

But ultimately, whether a machine is being truly creative may not matter outside of philosophical debates. The artistic results that computers will be able to produce, whether in the fields of music, art or literature, are only going to get better and better. If audiences approve of the output, will many people care whether art is produced by a troubled genius or lines of software code?

That is a question for another day. For now, neurologists will continue studying the mysteries of the human brain and computer scientists will continue in their efforts to recreate them in software form. Even if true creativity has not been achieved yet, we can still marvel at the dream-like scenes created by Google’s Deep Dream Generator, enjoy software-crafted songs and grow frustrated in our efforts to beat a computer at chess.

The pace at which AI is developing is impressive regardless of its shortcomings. And it is easy to see where these remain most pronounced: a machine does not yet seem able to tell whether what it has produced is any good, or, indeed, have any concept at all of what it has created.

“The table is black to be seen, the bus crossed in a corner,” begins another section of 1 the Road. “Part of a white line of stairs and a street light was standing in the street, and it was a deep parking lot.” Gibberish? Perhaps – or maybe the avant-garde musings of a literary genius. After all, the opening of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake is arguably even less coherent, starting mid-sentence: “riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.”

Art will always be open to interpretation, discussion, praise and ridicule. No one can say precisely what creative works will be produced in the future, but it’s looking increasingly likely that they will be made by both man and machine.