The ice race: oil giants vie to be first to tap into Arctic black gold

There’s a mine of black gold beneath the Arctic – enough oil and gas to keep the world going for decades. Extreme weather conditions and infrastructural insufficiencies mean it’s near impossible to reach. But that hasn’t stopped people trying

Spitsbergen, Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic Sea. Extreme weather conditions and the relative inaccessibility of the region are among the factors complicating Arctic exploration

Tucked away among the Arctic’s ever-shifting jags of ice, hidden from the naked eye, are billions upon billions of dollars in black gold. The Arctic landscape, spanning the Barents to the Beaufort Sea and beyond, is home to a reported 30 percent of the world’s undiscovered natural gas reserves and 13 percent of its oil. Whoever conquers it will lay claim to 1,669 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and 90 billion barrels of oil – almost three times the annual global consumption.

Much of the prospective total, according to the US Geological Survey, sits offshore and is available for the taking, provided that those with suitably high ambitions come equipped with the necessary tools, know-how and – most importantly – resources to do so.

The challenges of tapping the Arctic’s resources are plain to see: a harsh climate, underdeveloped infrastructure, long project cycles…

Although the whole region accounts for as little as six percent of the Earth’s surface, it accounts for a disproportionately large amount of its resources. It is this abundance of hydrocarbons that has led energy companies to clamour for the rights to the region’s opportunities.

“It is only in the last five years that hydrocarbon development has actually been contemplated as a possibility, principally due to technological and navigational advances,” says Trevor Slack, Senior Analyst at risk analysis company Maplecroft.

“To varying degrees, Russia, Canada, the US, Norway and Greenland have all increased exploration and development activity on their relevant portions of the Arctic continental shelf.”

The overwhelming majority of the countries bordering the Arctic have granted energy companies licenses to explore offshore reserves: however, the exploration phase is only a fraction of the overall effort required to reap the region’s riches. The work required of those in the business can perhaps best be seen in the case of Royal Dutch Shell and the crisis that befell the Kulluk drilling rig late last year.

“What is failure but a bump on the road to triumph?” asked the company’s website soon after its 266ft rig ran aground off the Alaskan coast: an event that resulted in an impairment charge of $200m.

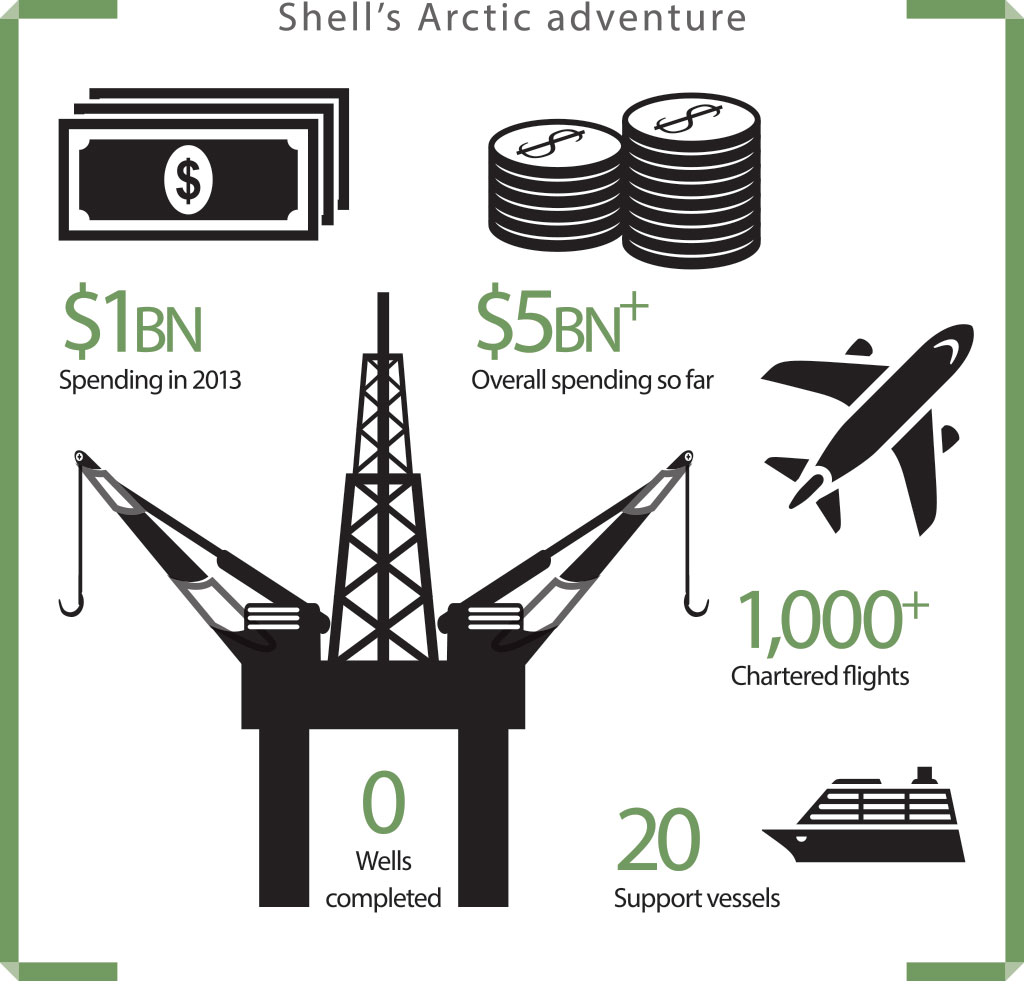

The failed expedition constitutes a slither of the oil giant’s overall Arctic spending, which is already upwards of $5bn, and yielded very little in the way of returns. Despite introducing an armada of 20 support vessels, chartering well over a thousand dedicated flights, and unloading $1bn on the project in the last year alone, the Anglo-Dutch powerhouse is yet to complete a single well in the region.

While these circumstances could well be considered a failure, they could just as easily be seen as par for the course, as the extraction of Arctic oil and gas ranks among the most expensive business opportunities in the world.

An expensive endeavour

$500m

Predicted cost of drilling one oil well in the Arctic

$100bn

Potential spending in the Arctic by 2022

“Oil spill risks, high extraction costs, doubts over the amount of commercially recoverable reserves, and a precedent of cost overruns and delays combine to raise questions about the commercial viability of some proposed Arctic projects,” reads a Greenpeace report into Arctic exploration risks. “The drilling conditions facing oil companies operating in the Arctic are some of the most challenging on Earth.”

Breaking the ice

The challenges of tapping the Arctic’s resources are plain to see: a harsh climate, underdeveloped infrastructure, long project cycles, spill containment and recovery risks, and conflicting sovereignty claims, to name but a few. The complications have caused some to question whether the investment is worth the costs – whether they be financial or environmental.

In the months preceding the Kulluk rig disaster, Total became the first major oil company to publicly denounce offshore exploration in the Arctic, as the company’s CEO Christophe de Margerie expressed fears about the potential damage of a spill. “Oil on Greenland would be a disaster,” he said in an interview with the Financial Times. “A leak would do too much damage to the image of the company.”

Total’s stance on the matter is very much the exception, however, with various competitors – including ExxonMobil, Rosneft, Eni and Statoil – having committed a great deal of time and money to the Arctic endeavour. Shell, for its part, has cancelled plans to resume Arctic drilling this summer. The company’s new chief executive, Ben Van Beurden, admitted the company had “not always made the right capital choices” and that its exploration programme was “under review”.

However, the company will be subject to far closer scrutiny than before in light of its previous failings. Shell’s return to the Arctic – however delayed – will be watched by environmentalists, whose concerns for the surrounding environment need not be explained, as well as industry rivals, who will be keen to know whether or not the region’s treasures can be tapped.

Exploration obstacles

A US appeals court recently ruled the Alaskan government acted illegally in granting exploration rights to US Arctic waters. The region was sold for $2.66bn in 2008, of which $2.1bn was paid for by Shell, and has since been hotly contested by local and environmental groups, who claim the consequences were ill conceived and its environmental impact sorely underplayed.

Development costs and other such obstacles have also hindered the progress of Statoil. Late last year, the Norwegian firm expressed concerns about the challenges of exploring and extracting Arctic hydrocarbon reserves.

“Logistical difficulties, regulatory hurdles, jurisdictional tensions, environmental opposition and, above all, extremely inhospitable climatic conditions will ensure that oil and gas activity in the region remains problematic, complex and expensive,” says Slack.

“Cost is probably the most important factor, with Statoil estimating that the cost of drilling one oil well in the Arctic could be as much as $500m. This is likely to be prohibitive for most companies in the current climate, with some analysts predicting that the price of crude could drop in the medium term.”

Statoil’s Exploration Chief Tim Dodson spoke at a climate change conference last year about a few of the issues facing oil companies in the Arctic.

“We don’t envisage production from several of these areas before 2030 at the earliest; more likely 2040, probably not until 2050. I think what we have to realise is that the challenges our industry faces in the Arctic are at least as significant as we thought they were just a couple of years back, but they’re not insurmountable.”

Arctic resources

1,67trn

Cubic feet of natural gas

90bn

Barrels of oil

Edinburgh-based Cairn Energy, meanwhile, has announced it is deprioritising its Greenland operations. It spent over $1bn in the region and didn’t make a single commercial find. Many believe the inadequate infrastructure and tumultuous weather conditions, combined with the falling price of oil and gas, to be obstacles too big to be overcome. Theses circumstances mean the financial benefits can only be marginal at best, until stratospheric sums of capital are poured into developing the region.

Charlie Kronick, Senior Climate Advisor at Greenpeace UK, is sceptical.

“[It] is impossible to drill safely for oil in the ice-covered waters of the Arctic – the potential impacts on local livelihoods and biodiversity are uncostable. It would be literally impossible – for both technical and environmental reasons – to clean up after the inevitable spill, while the level of climate change that would result from successful (in economic terms) drilling there would be catastrophic.”

A report conducted by Lloyd’s and Chatham House found investment in the Arctic could reach $100bn by 2022, as companies scramble to gain a foothold. Richard Ward, Chief Executive at Lloyd’s, said: “Business activity in the Arctic region is undeniably increasing, and the impact of climate change means that this is likely to grow significantly in the future. But as new opportunities open up, decisions on exploiting them need to be made on the basis of as full an understanding of the risks as possible.”

Regardless of the opportunities, it is crucial that businesses align their goals with those of local governments, communities and the environment. In addition, it’s important that those partaking in Arctic oil and gas exploration take into consideration, and account for, the worst-case scenario if they are to be adequately equipped for costs that could quite easily ensue.

Ward said: “The businesses which will succeed will be those which take their responsibilities to the region’s communities and environment seriously, working with other stakeholders to manage the wide range of Arctic risks and ensuring that future development is sustainable.”