The resource curse: why countries that have so much, often have so little

Large reserves of natural resources are not always the boon they appear to be; they can bring corruption and contraction if a country’s wider economy does not benefit

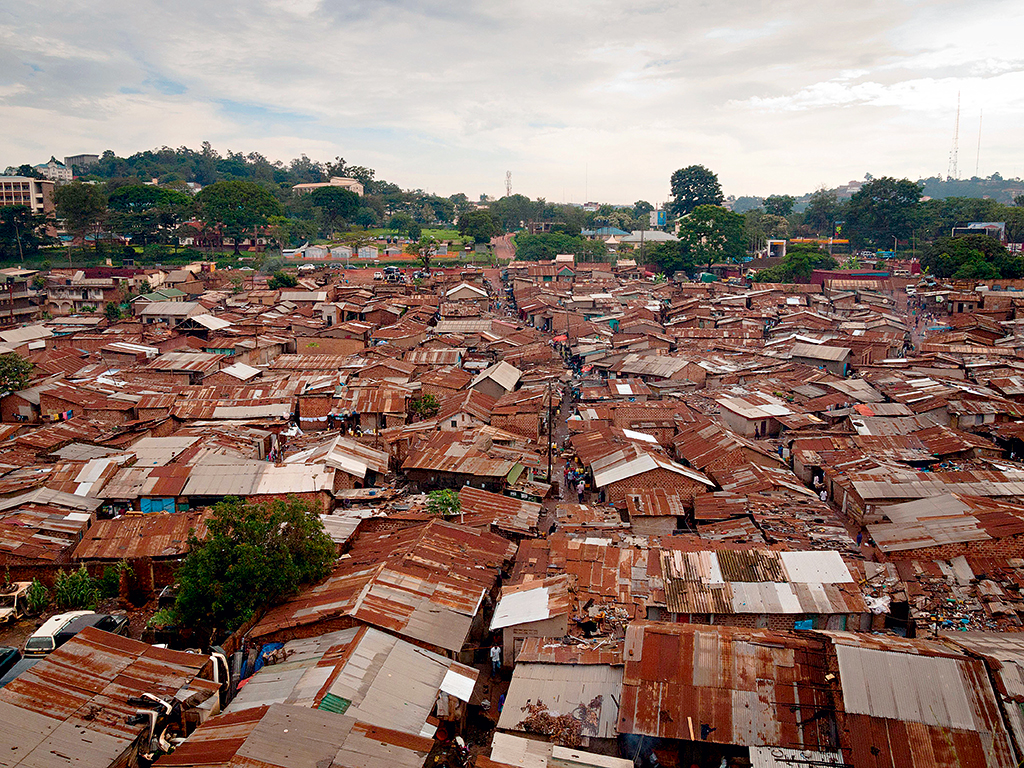

The Kataanga slum in Kampala. Falling oil prices have left Uganda one of the most heavily indebted countries in the world, despite its abundance of natural resources

An abundance of natural resources brings economic prosperity, particularly in developing countries where those raw materials often represent the single biggest contributor to state finances. Or so the theory goes.

On the one hand, countries rich in fossil fuels and similar such commodities have the potential to realise broad-based and sustainable gains, but the issues crippling those same parties suggest there are many problems associated with the issue. For years, it has been said that resource wealth plays a positive role in economic development, yet there is strong evidence to suggest those without often perform better than those with a lot of natural resources.

[A]cademics have largely failed to pin down the exact nature of the resource curse, as the situation varies extraordinarily from case to case

The resource curse hypothesis is used to describe just such a situation, whereby an abundance of natural resources can lead to corruption and stagnation, or even economic contraction. “It increases the exchange rate, thereby stifling other export industries. It breeds corruption and embezzlement. It deflects productive energy and talent towards rent seeking and away from innovation and entrepreneurship. It causes autocracy, civil war and international war”, says Francesco Caselli of the London School of Economics.

Stifling development

There is nothing inherently shortsighted about an economy that chooses to double down on its strengths, but doing so on non-renewable criteria contains risks inasmuch as those resources are finite. The simple truth that prices are, by their nature, unpredictable means there is often inconsistency when it comes to making policy decisions. Such is the complexity of the issue at hand that academics have largely failed to pin down the exact nature of the resource curse, as the situation varies extraordinarily from case to case.

“Managing natural resource wealth is fraught with difficulties – some economic, many political – and if not done well, can adversely impact macroeconomic performance in the short and long runs”, according to an IMF report entitled Boom, Bust, or Prosperity? Managing Sub-Saharan Africa’s (SSA) Natural Resource Wealth. “Data from the sub region suggests that such a curse has been present to some degree but has diminished since 2000, although the broad economic and social indicators point to continued weaknesses that could be attributed to poor natural resource management.”

Africa, particularly Sub-Saharan Africa, is the perfect example of how abundant resources can stifle development and distract governments from the central task of ensuring long-term prosperity. Looking only at the past 50 years, the continent has made a name for itself as a region rich in natural resources, though one where its citizens are severely handicapped by a low-growth climate and endemic corruption. With little incentive to raise taxes or focus on sectors aside from fossil fuels, plentiful resources have succeeded largely in crippling once-fruitful economies and shrinking government responsibility.

“Being resource rich is a challenge because there’s enormous potential for people to profit personally”, says Chris Beaton, Research and Communications Officer at the International Institute for Sustainable Development. “Political factions can grow around who-helps-who-get-rich and average citizens may not receive the full benefits of their country’s resources – or indeed, any of the benefits at all.

“In turn, this can lead to deep mistrust of government that is hard to reverse. The relationship between resource riches and corruption is very well documented. The greater the value of the resources, the greater the incentive for corruption, so fossil fuel resources, particularly crude oil, are of course often associated with poor governance. But it’s only a question of increased risk; it isn’t guaranteed the two will come hand-in-hand. Some oil-exporting countries, such as Norway, score amongst the least corrupt in the world.”

Venezuela, Iraq, Nigeria and Russia, for example, are all rich in oil, but all occupy low positions on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index for 2014. By choosing to over rely on the distribution of oil-derived revenues equally, guilty parties run the risk of throwing away opportunities for economic and social development. “Supporting populists who distribute largesse to the masses out of oil revenues may not pay in the long run, as, while they do so, the populists destroy the rest of the economy. When the oil riches dry up, the handouts end, and there is nothing else to turn to”, says Caselli.

Clearly, the natural-resources-equal-growth equation is far too simplistic, and the sensible management of these resources, or lack thereof, is the single-biggest determinant in bringing either success or failure. According to a report by the UONGOZI Institute, entitled Managing Natural Resources to Ensure Prosperity in Africa, “How natural resources and associated revenues are managed will have a profound impact – for good or for bad – on the course of African economies and the prosperity of Africans. For the depletion of natural assets to be converted into sustainable national development, a series of decisions have to be made sufficiently right”.

The bad

In Uganda, the realisation late last year that the country’s oil reserves were 85 percent greater than first thought brought a renewed focus on the country’s dealings, as those concerned looked to neighbouring nations for proof of how similarly impressive discoveries had failed to bring prosperity. The revised findings, which also showed evidence of commercially viable natural gas deposits, point to reserves of approximately 6.5 billion barrels and a host of new opportunities for the oil-rich nation. However, perhaps more significant is that the discovery has landed the East African nation in trouble even before production has come on line.

Since 2008, the Ugandan government has thrown a colossal amount of money at the oil and gas sector in the hope that doing so might bring a greater measure of development to the predominantly low-income nation. However, the dangers of relying on often-volatile and finite resources have become clear: falling oil prices have turned Uganda into one of the most heavily indebted countries on the planet. From 1990 to the early 2000s, Uganda was making steady progress, but its economic backslide and rising levels of corruption began in 2007, coinciding with oil discoveries. Following in the footsteps of Nigeria, Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda is the latest nation to suffer the effects of the resource curse.

“The wheel of fortune turns”, says Beaton. “Oil importers may currently be enjoying the benefits of low prices while resource-rich nations struggle, but they can be sure – perhaps not today, perhaps not tomorrow, but eventually – prices will go up again. They should use this time of good fortune to prepare well for the next time of need.” Similarly, resource-rich countries must use oil-derived revenues to develop human capital, improve infrastructure and expand upon sectors aside from fossil fuels.

The good

An abundance of natural resources does not necessarily condemn any host country to an ill fate, and there are numerous examples of governments that have succeeded in spreading the wealth more evenly. Norway is perhaps the most obvious pick. Top of the United Nations Development Programme’s Human Development Index and in the running for the highest GDP per capita in the world, sensible resource management has lifted the country’s prospects far and above what they were prior to any major oil or gas discovery.

Alaska is one of the lesser-known resource majors that have succeeded in more evenly distributing oil-derived revenues. In 1976, as the country’s pipeline construction neared completion, policymakers established the Alaska Permanent Fund to ensure proceeds would benefit sectors of the economy aside from oil. According to the constitutional amendment: “At least 25 percent of all mineral lease rentals, royalties, royalty sales proceeds, federal mineral revenue-sharing payments and bonuses received by the state be placed in a permanent fund, the principal of which may only be used for income-producing investments.”

The ‘wealth distribution experiment’, so-named by the Basic Income European Network, last year distributed a $1,884 dividend to over 640,000 citizens and, in doing so, lifted the total sum paid out over the fund’s life span to more than $37,000 per Alaskan. Though unconventional, the fund is now a tried and tested means of putting oil riches towards societal and economic gains, and the mechanism has transformed what were diminishing oil riches into a sustainable financial asset.

The fund is far from the only solution to fighting the resource curse, and, aside from generally good governance and sensible long-term planning, analysts have proposed alternative systems in which a share of the income is gifted directly to citizens. The Centre for Global Development believes abiding by this approach could create a “social contract” between citizen and state, “with a personal stake in the government’s budget, the citizens could then hold the government accountable for providing goods and services with their taxes”.

Choosing to distribute resource-derived profits more evenly means nations need no longer neglect unrelated sectors of the economy, and officials found guilty of hoarding or misspending resource capital will be held to greater account. Too often, natural resources put the state at the centre of the economy. Putting proceeds into the hands of citizens could instead reduce government corruption and create a more balanced economy.