How does the music industry make money?

Music streaming services such as Spotify are becoming increasingly popular, but many artists think they don’t pay enough

The music industry has shifted towards a subscription model, where listeners no longer own the music they love

In 1937, the Chicago branch of the American Federation of Musicians arranged a strike in the city that saw musicians withdraw their services in protest at the proliferation of ‘canned’ music. Such had been the rise in the use of recorded music, which was subsequently played on the radio, that musicians who had previously made their money through performing live were now finding work hard to come by.

It seems strange now to think of musicians being against recorded music, but back then it was a relatively new concept and many artists were paid minuscule amounts of money in comparison to what they earned performing live. The idea that people could own recordings of music, which they could then play as and when they liked, meant live musicians were reduced to getting their income from all-too-rare performances, or the meagre royalties that sales and radio plays generated.

The consequence of the ban was a loss of $125,000 in recording fees for Chicago musicians. It did little to stop the rapid growth of record companies and the demand from the public for recorded music. Such was the appetite that it soon became the norm for people to have large collections of music, while record companies became all-powerful industry bodies that decided who became successful.

Ownership vs rental

The idea of ownership of music by consumers is one that has only emerged since recorded music became popular. Consumers have come to assume they own the content they have purchased – and this also includes films and books. However, the rights holders of such content tend to be a combination of record labels that distribute it or pay for it to be made, and the artists who created it in the first place. The user is, in legal terms, merely licensing it.

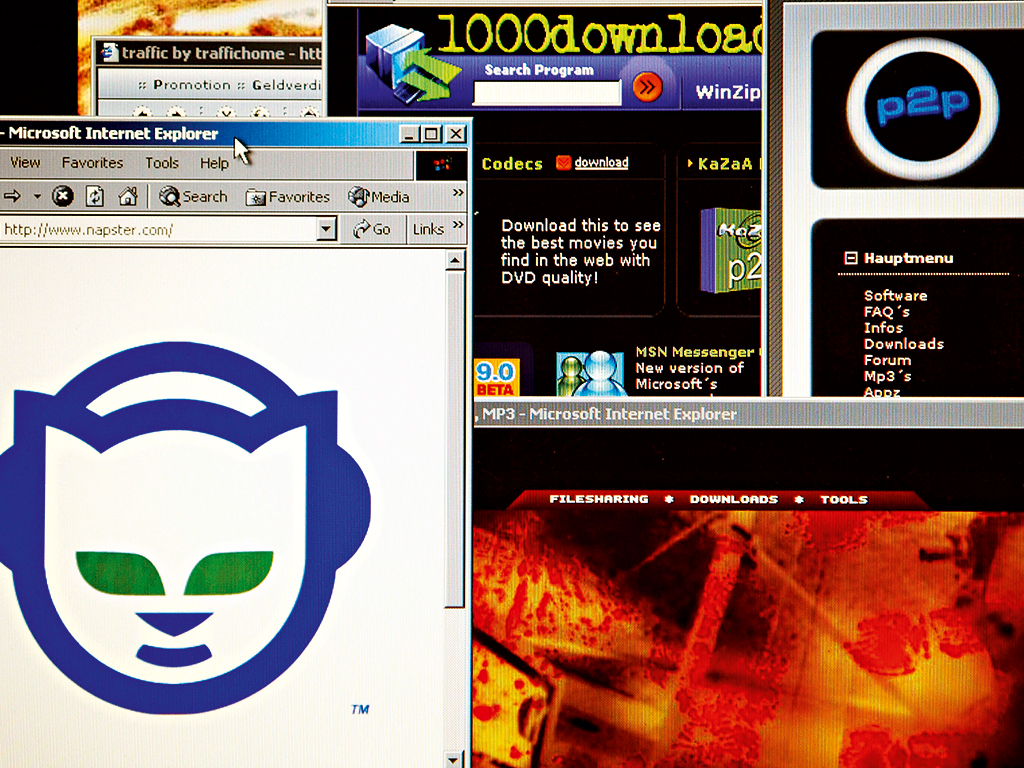

Some consumers have thought that, once they purchased the content, they’re free to do with it as they choose (such as sharing it with others), but the owners of the copyrighted material have pursued such practices with vigour. Policing the use of licensed material became much harder, however, when the internet created an easy way of sharing content quickly, freely and in a manner difficult to detect. Content rights holders found it hard to keep up with the many ways that were emerging to share their work.

Although streaming services seem to be helping in the fight against piracy, they also mean listeners or viewers don’t have as much control over the content as they used to

The dominance of record labels began to wane when the internet opened up alternative possibilities for musicians and fans who felt they had been short-changed by a bloated and cynical industry. In their efforts to address the decline in sales caused by piracy, large and powerful rights holders scored a number of public relations own goals by going after individuals – including young children – who had traded their work.

The record industry was slow and confused in its reaction to these changes, struggling to find a meaningful and steady form of income with which to replace dwindling sales. It was hoped the music-buying public would be content with downloadable files from the likes of the iTunes Store; sustaining the content model of the labels that owned and distributed music, but turning it digital.

However, while the number of music files being legally downloaded has risen sharply over the last decade, a range of alternative services have emerged to challenge the way in which consumers access such content. Streaming services such as Spotify and Rdio have attempted to turn people away from music ownership and towards a rental system based around advertising and subscriptions. In the world of film and television, Netflix has begun to make serious strides in cutting the number of pirated films downloaded, while presenting a challenge to the physical market.

The fight against music piracy

While music piracy is a long way from being eradicated, services such as Spotify and iTunes, which allow easier access to music, are helping to address the problem. Recent research has shown these services are both growing rapidly and curbing piracy. In Norway, research by Ipsos MMI found the number of songs pirated in 2012 was 210 million – a mere 17.5 percent of the 1.2 billion copied in 2008. Piracy of film and television had also halved in that period. These figures could reflect a trend for the rest of the world, one in which streaming is killing off piracy and bringing in revenue for rights holders. But many argue the amounts paid to the holders – particularly by Spotify – are neither enough nor fair to newer musicians with fewer fans.

Fall of the Norwegian pirates

1.2bn

Songs pirated in 2008

210m

Songs pirated in 2012

17.5%

Decrease in music piracy 2008-12

The music industry has taken its time in finding a suitable model, but the ease of use and extensive catalogue that the leading streaming services offer mean there is now a viable alternative to piracy. However, there needs to be regulations on copyright that are enforced, says Julian Hewitt, a music specialist and partner at Australia-based Media Arts Lawyers. He told The New Economy: “It seems like the industry will not litigate, and so are looking for political assistance to help curb piracy. Certainly, if, as a society, we still think there’s a place for copyright – and that’s a position I very strongly support – then we need to uphold it. The market is competitive and legitimate services are not expensive – it’s the same with filmed content – so hopefully piracy will become inconvenient enough to kill itself off – but it has cost our artistic community immeasurably.”

Although streaming services seem to be helping in the fight against piracy, they also mean listeners or viewers don’t have as much control over the content as they used to. Subscribers are still licensing the songs, but they have less control over what they can do with them – such as copying them and distributing them among their friends. Some research has even shown people’s attitudes towards ownership of music appear to be changing. However, what changes now is the amount of money recouped from each listener – much less initially than from a physical or download sale. This has implications for artists and rights holders that have grown dependent on these sales.

Does Spotify pay artists enough?

The debate over what Spotify pays artists has raged since the company was launched in 2008. According to some artists, Spotify pays as little as $0.004 for every play of a song. The rate has been criticised by many for being too low, particularly as those without a large fan base are seeing their work hosted on a service that allows people an unlimited number of plays. The debate had begun to simmer down in recent months, following a number of high-profile signings, including Pink Floyd and Metallica. However, others, such as Coldplay and The Beatles, have remained off the service, and more are becoming disgruntled with the low royalty fees.

Spotify stats

$1bn

Estimated amount paid by Spotify to rights holders at end of 2013

$0.004

Rights holder payment per play

$0.70

Rights holder payment per download

Nigel Godrich – the acclaimed producer of artists including Radiohead, Beck and Paul McCartney – reignited the debate over what Spotify pays artists in July when he announced on Twitter that he was removing his music from the streaming site. Godrich said the recently released album by Atoms for Peace – a project with Thom Yorke from Radiohead and Flea from the Red Hot Chilli Peppers – was taken down from Spotify in protest at the low royalty fees the service pays new artists. Describing the rate new artists get paid, Godrich – backed by Yorke – said: “It’s an equation that just doesn’t work.”

Mark Kelly, keyboardist for English band Marillion, disagrees, however. He told The New Economy that most of the songs Spotify pays out for are newer material: “According to Spotify, most of the money they pay out is for new songs and not the old catalogue artists like Marillion and Radiohead. Furthermore, they pay through 70 percent of their revenue, as do Apple.”

Spotify responds

In response to the comments from Godrich and Yorke, a spokesman for Spotify said the firm was merely at the early stage of developing its service: “Right now, we’re still in the early stages of a long-term project that’s already having a hugely positive effect on artists and new music. We’ve already paid $500m to rights holders so far, and by the end of 2013 this number will reach $1bn. Much of this money is being invested in nurturing new talent and producing some great new music.”

There is a stark difference between the lifetime fees Spotify generates for artists and the one-off payment received for a single purchase or download. Although the rate of $0.004 per play is small, in the long-term it could net the artist more than the $0.70 for each individual download. Also, as Spotify is a relatively new service with fewer paid-up members than iTunes, it is likely that, as it increases in popularity, it will be paying out much more to rights holders.

However, much of the discontent from artists over what Spotify pays to rights holders is to do with who owns the rights and who negotiated the fees in the first place. The record labels that saw their sales and influence dwindling at the turn of the century have invested heavily in Spotify – including through equity stakes. They are happy to negotiate low-rates of royalties safe in the knowledge their extensive back catalogues will earn them money for years to come. Struggling artists, on the other hand, might not be able to last quite so long with such a paltry – if steady – stream of income.

One label that has a different stance to many is the Beggars Group, which pays its artists 50 percent of streaming revenue. According to Kelly, all labels should follow Beggars’ lead: “Part of the problem is that many artists don’t own their rights and are being paid from streaming income as if it were a physical sale. All labels should follow the lead of Beggars Group and pay artists 50 percent of all streaming income. That, coupled with a 10 or 20-fold increase in paying customers, would mean that streaming would become a valuable source of income for artists and labels alike.”

Hewitt says streaming models are likely to be more beneficial to artists in the longrun, although it’s still too early to make a proper estimate of the effect: “Conceptually, the streaming models are incredibly fair because, instead of paying for the upfront purchase of music, your subscription fees are being distributed by plays – so the music that has the most profound place in your life will be paid the highest share of your fees. Doing a ‘per play’ calculation on what artists get paid at this point is pretty nebulous because the subscription pool is still very low.”

Embracing technology

Clearly, new technology is not going away, and the industry – both artist and label – needs to embrace it. Radiohead’s manager, Brian Message, spoke shortly after the comments made by Yorke and Godrich, saying the industry needed to work with firms such as Spotify to develop the best possible way of remunerating artists.

Solving the problem of online music piracy has troubled the industry for well over a decade

He said: “It’s not black and white: it’s a complicated area. There [have] been over 20 attempted reviews of copyright and how it operates in the internet era, and there’s been no satisfactory solution to it. The bottom line is technology is here to stay and evolution of technology is always going to go on. It’s up to me as a manager to work with the likes of Spotify and other streaming services to best facilitate how we monetise those [platforms] for the artists we represent. It’s not easy, but it’s great to have the dialogue.”

Hewitt adds that streaming services are still being developed: “The model is still being refined – the level of royalties paid through from services like Spotify to the artists, labels and publishers is a negotiated rate that isn’t set in stone ad infinitum.” However, Hewitt also says the music industry needs a strong set of competing services to give the consumer choice and ensure a healthy market: “I think it’s important that there are competing services otherwise the music industry runs the risk of another iTunes: a service provider with enough market share and power to screw down the creatives.”

One service that is not paying enough to artists, according to Kelly, is YouTube. He says: “All artists, new and old, suffer from the biggest streaming service, YouTube, paying an insulting amount to the people who made YouTube the success it is: the creators.” Some artists are even less enthusiastic about online music, with Talking Heads frontman David Byrne telling the Guardian in October: “The internet will suck all creative content out of the world.”

Solving the problem of online music piracy has troubled the industry for well over a decade. Kelly says these new services are gaining traction because of their ease of use compared to file-sharing websites: “The user experience for people who access content through piracy is terrible. That’s why people are willing to pay for Spotify and iTunes… I think there is a place for regulation too, in order to make piracy an even worse experience and more hassle than it’s worth. The place to apply the pressure is the delivery system: the ISPs. They have been profiting from delivering creative content at ever-faster speeds while not paying us, the creators, a bean.”

The digitalisation of music

Alternatives for artists

Finding an alternative method has troubled both artists and executives. With technology forever evolving, it’s increasingly difficult to predict what method of music consumption will be prevalent in a few years. From the perspective of an artist, some have looked to give away their songs, hoping their income will come from increased touring and merchandise sales. Others have used crowd-funding services such as Kickstarter and Bandcamp to raise money.

Having spent their career at industry giant EMI, Radiohead decided not to sign a new contract, instead choosing, in 2007, to offer their album In Rainbows to fans for whatever they felt like paying. Although they never released the official figures, it’s thought the average amount spent by fans was £4, and that it proved more profitable than their final album at EMI, Hail to the Thief. Radiohead didn’t stick to this model, however. In 2011, the band released a new album in the traditional manner, through independent label XL Recordings.

The consequence of this shift in how people see their media content – emphasising the license over actual ownership – might, in fact, have a profound effect on the control an artist can have over that music. It might make consumers realise the entertainment they enjoy is not really theirs to distribute and share, bringing to an end over a decade of rampant piracy.