A trailblazing year for the Nobel Prize

This year’s winners included the first woman to be awarded the prize in the 21st century, and the oldest person ever to win the prestigious accolade

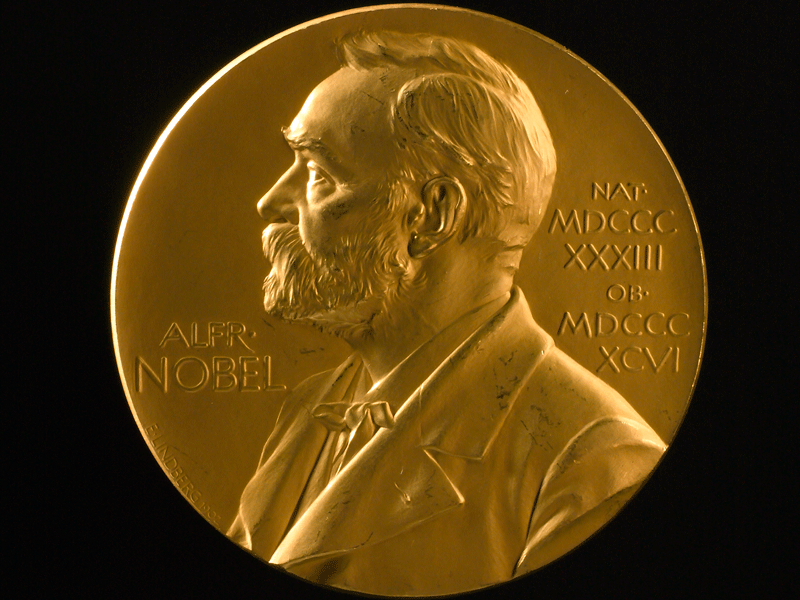

The Nobel Prize medal, showing the image of Alfred Nobel and the years of his birth and death. The distinguished award was established in 1895 by the will of the influential Swedish scientist

As the 2018 Nobel Prize winners were announced, one thing became clear: this a year of firsts. Each of the scientific prizes, awarded over the course of three days at the beginning of October, has broken the mould in terms of the research it has recognised, as well as the scientists behind that research.

Each of the scientific prizes has broken the mould in terms of the research it has recognised, as well as the scientists behind that research

The Nobel Prize was established in 1895 by the will of Swedish scientist Alfred Nobel, and is given for outstanding contributions in the scientific, literary and humanitarian fields. As well as being an extremely prestigious accolade, it has long been seen as the definitive voice in recognising not only scientific research itself, but also the impact that it has on the world we live in.

A physiology first

The first of this year’s awards, announced on October 1, was the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine, which was awarded to James Allison and Tasuku Honjo for their ground-breaking immunotherapy research.

The work of the two scientists, who are researchers at the University of Texas and the University of Kyoto respectively, has led to a change in the way certain cancers are treated.

Allison and Honjo’s research concerns proteins known as ‘checkpoints’ which act as brakes, preventing immune cells from harming healthy tissues. The scientists discovered that reprogramming these ‘checkpoints’ could produce remarkable results in cancers that had previously been considered untreatable. The new treatment, which stems from the results of their research, is known as the immune checkpoint blockade, and works by effectively switching off the brakes on immune cells, allowing them to attack cancerous cells.

This is the first year in the history of the prize that it has been given to an oncological innovation. The Nobel Assembly of Sweden’s Karolinska Institute, which delivered the award, described the research as “a landmark in our fight against cancer” in a statement.

Allison said: “I’d like to give a shout out to all the [cancer] patients out there to let them know we’re making progress here.” Honjo, who began his research after one of his medical school classmates died of cancer, proclaimed: “I want to continue my research … so that this immune therapy will save more cancer patients than ever.”

Breaking records

The announcement of the Nobel Prize for Physics on October 2 was a timely recognition of the contribution that women make to the discipline, being the first time in 55 years that the award has been given to a female scientist.

Professor Donna Strickland is the first woman to receive the prize since Maria Goeppert-Mayer in 1963. She is also the third woman in history to be given the accolade, the first being Marie Curie in 1903.

Strickland told a press conference: “We need to celebrate women physicists because we’re out there. I’m honoured to be one of those women.”

Professor Strickland will share the $1m prize with two male colleagues, Dr Gerard Mourou and Arthur Ashkin. Strickland and Mourou were honoured for their work in creating the shortest and most intense laser pulses known to man, which are now widely used by laser eye surgeons across the world.

Ashkin was rewarded for his invention of ‘optical tweezers’ that can grab living cells with laser beam fingers. At 96, he is the oldest person to ever win the accolade.

Pioneering proteins

The third and final scientific award, announced on October 3, breaks yet another record in the history of the Nobel Prize. British scientists George P Smith and Sir Gregory P Winter, together with American scientist Frances Arnold, were jointly awarded the prize for Chemistry for their pioneering work on proteins.

Professor Arnold performed the first ever ‘directed evolution’ of enzymes, which are proteins that catalyse chemical reactions. By controlling their evolution, scientists are able to manufacture all kinds of substances from pharmaceutical ingredients to biofuels.

Arnold also reflected on her status as an experimental female chemical engineer, and how that affected her perception in the world of chemistry. She said: “25 years ago, it was considered the lunatic fringe. Scientists didn’t do that. Gentleman didn’t do that. But since I’m an engineer and not a gentleman, I had no problem with that.”

Dr Smith and Sir Winter were honoured for their development of a process called ‘phage display’, which is used to develop new antibodies. The process has been used to create treatments for autoimmune diseases, arthritis and metastatic cancer.

As more innovations come to the fore, future scientists will be better equipped to develop treatments and cure diseases in ways that were not previously thought possible. Perhaps this is a sign of things to come, with more records to be broken with each subsequent year of the Nobel Prize.