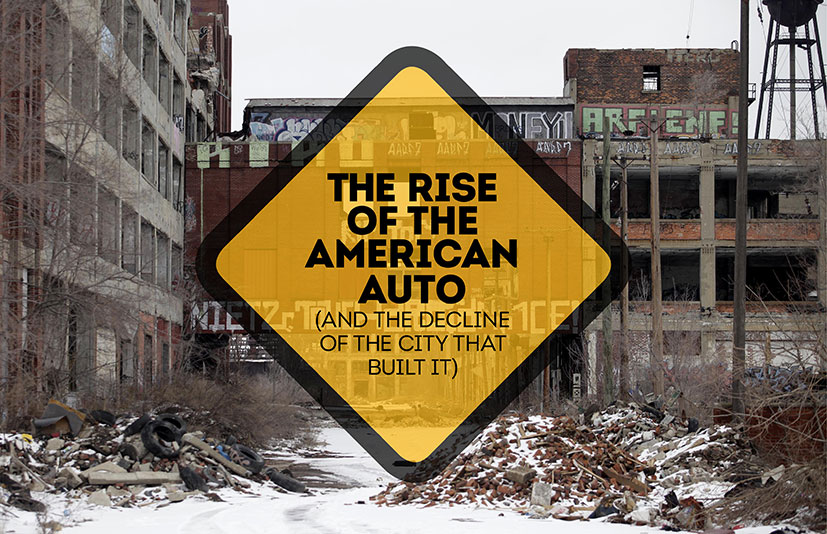

Detroit hits rock bottom

As Detroit continues to tumble down a steep slope of decay, the automotive industry it shaped is reaching unimaginable heights of success abroad

In the 1950s, the city of Detroit rightfully claimed to be the American dream incarnate. People from all walks of life travelled great lengths for an opportunity to work in one of the city’s many thriving automotive factories. Thanks to the innovative vision of rising titans like Henry Ford, the city of Detroit quickly became the world’s car capital. Companies such as Ford and GM quickly consumed the competition, and the American motor industry all but conglomerated within the sprawling confines of Detroit and smaller nearby towns like Flint and Dearborn, Michigan. In the same way that Hollywood is synonymous with the entertainment industry, Detroit became a symbol of America’s booming auto trade. With the prosperity of new factories and new jobs came a surging population and better quality of life. At its peak in the early 1950s, Detroit grew to become America’s third-largest city, with 1.8m residents. It boasted one of the highest median wages in the country, and a substantially better standard of living than most other cities. This fairytale rise only made the city’s imminent and apocalyptic fall even harder.

The decline of blue collar automotive employment across the board in Detroit is the number one factor responsible for the devastation of the city and its people

Today, Detroit lays in ruin. Its population has deteriorated by over 60 percent, and the people who remain there live in misery. One in five residents are unemployed and have no prospects of work or education. Over 80,000 buildings have been abandoned, and the burnt-out skeletons of once-thriving factories are slowly being reclaimed by nature. This sprawling abandonment has led to more dynamic issues. Because of dwindling public revenues, city services in Detroit are the worst in America. The average police response time to an emergency is almost an hour, whilst only one in three city ambulances are currently in service. Forty percent of Detroit’s streetlamps don’t work, and its metropolitan area has more crime per capita than anywhere else in America. Racial tension plagues the city like a festering wound, and in July, fate added insult to injury after city officials were forced to declare the largest municipal bankruptcy in US history. Things have never been worse in Detroit, and residents are split as to whether the city has even hit rock bottom yet. What everyone does seem to agree on, however, is the source of Detroit’s decay.

“The decline of blue collar automotive employment across the board in Detroit is the number one factor responsible for the devastation of the city and its people,” says George Steinmetz, a professor of sociology at the University of Michigan. “Ford was absolutely key to Detroit’s people.”

Therein lays the problem: Detroit may be the Motor City; however, the automotive industry outgrew the city’s boundaries a half century ago. As demand spread across the globe, prolific manufacturers like Ford and GM scaled back production across Michigan and began opening factories closer to individual emerging markets. Factories were mechanised, and aggressive demands from powerful unions in Michigan led America’s great auto firms to lay off more American workers and seek help from abroad, instead.

This expansion outside Michigan brought a boom period for auto companies, whilst Detroit withered from memory. Although the American auto industry itself has gone bust its fair share of times over the past fifty years, it’s booming once again with the help of emerging markets in Asia. That makes life better for one or two people in Detroit; after all, GM’s world headquarters can still be found in the city’s dilapidated centre. It employs a good chunk of the town, too. Yet it seems most of the jobs in America’s auto industry have turned into white collar ones. In Detroit, low-skilled work in the auto industry is virtually non-existent. Meanwhile, America’s biggest car makers employ tens of thousands of blue collar workers in their shiny new Asian factories. That makes sense, as it appears the future for these once mighty traders rests weightily upon the shoulders of increasingly keen Chinese buyers.

East is east

Demand for high-quality western cars in the east has been on the rise for quite some time; however, the legendary (yet declining) automotive giants that emerged from Detroit were fairly late to the party. They’re certainly making up for lost time. Ford and GM are aggressively expanding their production capacities in China, and introduce a wider range of models to Asian buyers every year. Since 2010, the west’s biggest carmakers have invested over $38.4bn in China. It’s not hard to see why; this year, auto sales across the country are expected to surpass the 20m mark – a 16 percent gain on last year. After America’s auto giants all but collapsed in 2009, this exploding market is proving a game changer of sorts. Whilst auto sales in Europe and North America continue to shrink amidst recession, demand for western cars in China has single-handedly driven global sales figures, against all odds, to increase by 6.7 percent this year. According to Klaus Paur, the Global Head of Automotive at Ipsos, these shifting figures will only continue to rise.

We have a good plan for China and have been leveraging Ford’s global resources to deliver on that plan

“The US market is still important for Western, as well as Korean and Japanese, car makers,” he says. “Nevertheless, the current recovery in the US market will soon level out since car penetration is pretty much saturated there … Substantial growth markets are mainly in Asia, particularly in China, India, and the ASEAN region, which is why all car makers need to shift their attention to these markets in the East in order to expand their sales volumes in the longer term.”

No manufacturer has expanded into China more than Ford. America’s oldest automaker has seen its shares surge 31 percent so far this year, and its global sales have reached a three-year high. That success can be pegged almost entirely on surging demand for its models in China. Last year, the Ford Focus captured the hearts of Chinese consumers and was named the country’s single-most popular car of 2012. Ford plans to capitalise upon this popularity by introducing 15 new models in China by 2015. In order to accomplish this, Ford has invested heavily in new factories across China. Between 2010 and 2012, the American firm built five new plants in key cities throughout country, and invested almost $5bn across Southeast Asia in general. The investments have already brought in huge returns. In the first half of 2013, Ford’s Chinese sales skyrocketed by 47 percent. By 2015, the company plans to control a six percent share in China’s overall new-car market – and by 2020, executives are speculating that Chinese buyers will account for 40 percent of all the company’s global sales. If Ford continues along its current growth trend, that may turn out to be a conservative estimate.

“We have a good plan for China and have been leveraging Ford’s global resources to deliver on that plan,” says Claire Li, of Ford’s Chinese division.

Only in America

Ford’s shifting priorities illustrate a growing trend within the industry; however, it’s worth noting the manufacturer is also experiencing a resurgence of domestic sales. When Alan Mulally was asked by the Ford family to take over as CEO in 2006, the automaker was, much like Detroit, in near ruins. Yet unlike Detroit’s municipal leaders, Mulally immediately did some heavy mortgaging. He slashed costs, simplified the company’s portfolio and made increasing product quality one of his top priorities. That was easier said than done. Ford took another tumble in 2008 when the global financial meltdown hit America’s already declining automotive industry. America’s biggest automakers had grown complacent, and bad investments in volatile markets led corporate worth to plummet.

Incentives for luring manufacturing jobs back to Detroit need to be created but for that to happen the city needs to offer tax breaks, and for that to happen it needs relief from its crushing debt

Both GM and Chrysler had no choice but to accept government handouts to avoid closure. Ford was able to skate around a full-blown bailout; however, the company did secure a line of credit with the government just in case. Sales at all three companies declined, and even more jobs were shed in Detroit. That being said, the government’s auto bailout appears to have paid off. Shares in GM have increased by 28 percent this year, and Ford has reached a new era of prosperity. The firm’s latest models of cars and trucks have evolved into class leaders, and Ford’s first quarter North American profits for 2013 were the highest it’s ever had.

None of that prosperity has trickled down to the people of Detroit. Since America’s auto industry hit rock bottom in 2009, things have been worse than ever in the Motor City. After the bailouts, another 50,000 Detroit residents fled the decaying metropolis. The city government receives less than 70 percent of property taxes, and its abnormally high population of unemployed and greying residents has pushed the city to a breaking point. In July, city lawmakers officially filed for chapter nine bankruptcy. No one was surprised by the move.

“Detroit’s story has been terrible for 50 years. This is just the latest terrible thing to happen,” said Matt Fabian of Municipal Market Advisors. “This will make it hard for the city to conduct day-to-day business. It will drain a lot of time, it could put people off moving businesses to Detroit and it could last for years.”

It’s hard to say how many more years of decline Detroit can stomach. Yet if the city has any hope of prosperity, it lies in reindustrialisation. After all, only 18 percent of the city’s residents have a college education – a talent pool unable to fill desks at GM’s white collar global headquarters in downtown Detroit.

“Things will only improve if employment moves back into the city. But the city’s bankruptcy will only aggravate an already severe urban crisis,” Steinmetz says. “Incentives for luring manufacturing jobs back to Detroit need to be created but for that to happen the city needs to offer tax breaks, and for that to happen it needs relief from its crushing debt.”

Motor City no more

As the auto industry as a whole continue to refocus investments over to Chinese markets, there don’t appear to be many incentives capable of luring manufacturers back to Detroit.

Today, the city has just two car factories, and the health of America’s auto industry has little bearing on the daily lives of Michigan residents. The city’s penniless government can’t bet on receiving any additional aid from the industry it helped to build, and it has even less hope of getting any federal assistance. In fact, next year the Obama administration has proposed to give almost three times more monetary aid to the violent drug haven of Columbia – whose homicide rate per capita is actually 81 percent less than Detroit’s. For now, it seems Detroit is on its own. Therefore, if the city should ever hope to try and reverse its rampant decay, it must diversify its output.

Nearby Pittsburgh proves a rare example as to how this can be achieved. For decades, the steel capital was utterly reliant upon one industry – so when US steel crumbled under the weight of foreign imports and a declining auto industry, Pittsburgh faced rapid decline.

Between 1970 and 2006, its population plummeted almost 40 percent. Yet during this flight of residents, Pittsburgh’s municipal government adequately refocused city services and investments. Elsewhere, entrepreneurs helped the city to establish a new identity as an American capital for healthcare in technology. Residents invested heavily in higher education, and today Pittsburgh attracts skilled professionals and industry leaders from across the globe. It’s hard to say whether Detroit still has the resolve to perform such a massive makeover.

Detroit once embodied the American dream. It was the centre of an automotive dynasty, led by a group of industrial titans that helped to herald in a new era of global transportation. Yet as the city continues to fall further into an abyss of decline, that past is visible only in the crumbling bricks of factory skeletons. Detroit is no longer directly tied to the fate of America’s once declining auto industry – in fact, the worse things get in Detroit, the better things seem to get for American carmakers. Bearing that in mind, it’s fair to say that Detroit is no longer a motor city per se. Yet if it can learn from the successes of other rustbelt cities like Pittsburgh, it doesn’t have to continue on as a textbook example of urban decay, either. In the meantime, American auto giants like Ford will only continue to explore new markets and prosper. Yet Chinese cities should be wary of the new American car factories springing up and employing their residents. After all, if any single lesson can be drawn from Detroit’s woes, it’s that the America’s thriving auto industry is boom and bust personified.