Mobile phones are changing personal finance across Africa

The use of mobile money has exploded across Africa in recent years, but while some nations are setting the global agenda, political barriers and trust issues are causing others to lag behind

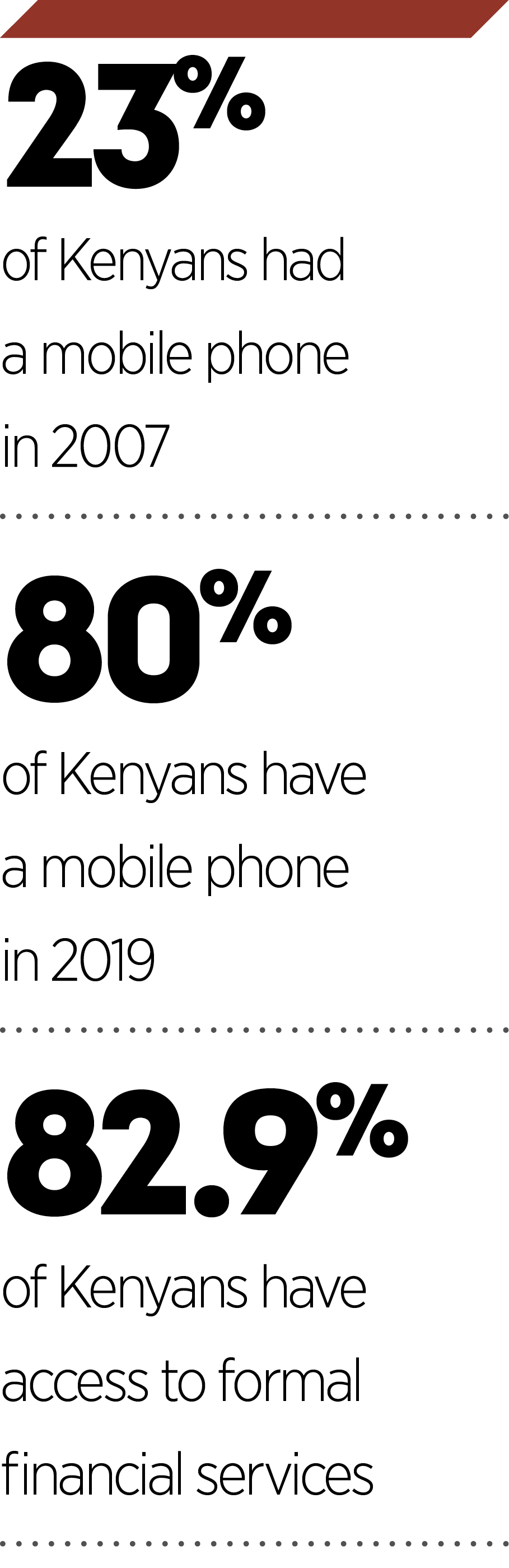

In 2007, 23 percent of the Kenyan population had a mobile phone, but in 2019, that figure has risen to 80 percent

When it comes to mobile money, sub-Saharan Africa is leaps and bounds ahead of other regions. Transactions using some sort of digital currency have a value of close to 10 percent of GDP, according to the World Economic Forum, compared with seven percent of GDP in Asia and less than two percent in Europe and the US.

But while statistics for the overall region paint a resoundingly positive picture, a closer look reveals that there are significant disparities between individual nations. In Kenya, for example, 73 percent of the population has a mobile bank account, and payment services such as M-Pesa dominate the country’s financial landscape. Yet in Nigeria, just six percent of the population use their phones for financial transactions, and 60 percent don’t have a bank account at all, despite the country being Africa’s largest economy.

The reason for this stark disparity lies predominantly in the difference between the two countries’ economic approaches. Tackling political barriers to reform is no doubt challenging, but it is a necessary and worthwhile endeavour: it will strengthen intracontinental trade and business ties, as well as make it easier for underbanked Africans to control their finances.

Leading the way

When M-Pesa launched in 2007, it was one of the first services to facilitate mobile transfers, not only in Africa, but worldwide. It had just two predecessors – Globe Telecom and Smart Communications – both of which began offering SMS transfers to customers in the Philippines in 2005. M-Pesa’s product, which was developed by mobile network Vodafone, allowed users to keep up to KES 50,000 ($480) in a virtual bank account, from which they could send funds to friends or relatives.

M-Pesa’s surprising success lies in the fact that mobile phone penetration has grown at an astonishing rate in Kenya over the past 10 years

For a country with an extremely large unbanked population, this was revolutionary. In 2006, just 18.5 percent of Kenyans had access to formal financial services; this was predominantly due to a lack of mainstream lender infrastructure, particularly in poorer rural areas. Banks had little motivation to establish retail branches or even ATMs in these locations due to the expense and a perceived lack of demand, but this perpetuated the issue of financial disenfranchisement, as residents did not have the means to travel to larger cities simply to access a bank. What’s more, it was unlikely they would be accepted for a bank account due to a lack of available funds or appropriate documentation.

It seems improbable that mobile money could have taken off so rapidly in such a disconnected and financially disempowered environment, but M-Pesa’s surprising success lies in the fact that mobile phone penetration has grown at an astonishing rate in Kenya over the past 10 years. This allowed the payments firm to gain a foothold in areas not previously touched by traditional financial services.

In 2007, 23 percent of the Kenyan population had a mobile phone, but in 2019, that figure has risen to 80 percent – an increase that was largely facilitated by investment in electricity and internet infrastructure at both a private and public level. Concurrently, the number of adults with access to formal financial services, including mobile payment services such as M-Pesa, has since risen to 82.9 percent.

Political opposition

Mobile adoption, while significant, is not the only factor that has contributed to the growth of Kenya’s digital financial landscape. Politics also played a key role: in 2007, Kenya’s traditional lenders heavily lobbied the government to crack down on M-Pesa, claiming the emergent firm was akin to a pyramid scheme and was overstepping the mark in launching financial services. They would have succeeded, too, had it not been for Bitange Ndemo, the permanent secretary of the Ministry of Information, Communications and Technology at the time, who made a strong case for the merits of mobile payments to President Mwai Kibaki.

Thanks to Ndemo’s persuasion, Kenya’s mobile money sector was able to thrive, but in other African nations the political environment has not been so conducive to success. In Nigeria, a regulation existed until 2017 that prevented network operators from transferring money for customers without the intervention of a bank. This was lifted by the Nigerian Government in the hope that it would help to boost the country’s financial inclusion rate, which stood at 40 percent at the time, according to World Bank research. However, the move was heavily opposed by traditional lenders, which had lobbied the government for years to prevent Nigeria’s powerful telecoms firms from entering the financial services sector.

In Zimbabwe, it has seemed in recent years as though mobile money could take off in a similar vein to Kenya. “Not as far as bitcoin or anything like that, but a very informal variant,” said Professor Stephen Chan, a professor in the Department of Politics and International Studies at SOAS University of London. “It was very much at a grassroots level, but the grassroots in Zimbabwe is very fired up [as a result of the country’s fragile economic situation] and very canny.” Any potential progress in the sector, however, has been quashed by the Zimbabwean Government. “The government was very reluctant to allow essentially a virtual economy to spring up, because it couldn’t control it,” Chan added.

Zimbabwe’s highly conservative minister of finance, Mthuli Ncube, has implemented a series of policies that have made it near impossible for payment firms to gain a foothold, the latest being the addition of a two percent tax on every transfer carried out via mobile. While Ncube claims this serves to prevent tax evasion, it also prices out many Zimbabweans from using mobile payment services. Following its implementation in August this year, Zimbabwe’s consumer rights association issued a statement claiming the tax will “not only burden the impoverished consumer, but will also drive the costs of doing business”.

Trust issues

Reticence to mobile money also comes from the people themselves, particularly in countries where traditional currency has been plagued by hyperinflation and corruption. In Zimbabwe, former prime minister Robert Mugabe’s overzealousness with the financial printing press contributed to one of the worst hyperinflationary episodes in global history, wiping out citizens’ savings and leaving the country without a stable national currency ever since. Kenya, meanwhile, was forced to discontinue its KES 1,000 ($10) note earlier this year after it emerged that it was routinely counterfeited. What’s more, according to Transparency International, more than a quarter of Africans have had to bribe an official to access public services in the past year, with the vast majority of such payoffs supplied in cash.

These deep-seated issues have not only eroded people’s purchasing power, but have also severely dampened confidence in both government and financial institutions. It’s little surprise, then, that the citizens of these nations have not embraced mobile money with open arms, as they have no guarantee that digital currency will not be beleaguered by the same problems.

Tackling these trust issues is crucial if mobile money is to succeed unilaterally across Africa, but nations will see the greatest success if they combine an anti-corruption drive with a comprehensive infrastructure investment programme. As for political opposition, M-Pesa’s success in Kenya has proved that mobile money has huge potential for good, particularly in terms of financial inclusion. This is the case not only for individuals, but also for small businesses, which are often a key economic driving force in rural areas. Allowing a private firm to provide those services – while an unfavourable choice for countries with highly conservative economic regimes – is a necessary trade-off in order to obtain the numerous benefits associated with mobile money.