FAANGs vs BATs: the US and China battle for tech dominance

The US and China are caught in a technological arms race, with companies on both sides investing heavily in cutting-edge solutions. Whichever superpower comes out on top could dominate the global economy for decades to come

Sophia, an artificially intelligent humanoid, has become a symbol of China’s progress in the battle to dominate AI development

China and the US are at loggerheads. President Donald Trump has claimed “trade wars are good, and easy to win”, while Communist Party leader Xi Jinping has committed his country to “a new phase of opening up”. Despite the countries’ opposing rhetorics, both have imposed tariffs on one another as trade tensions have escalated. The rivalry between these two superpowers, it seems, could come to define the 21st century.

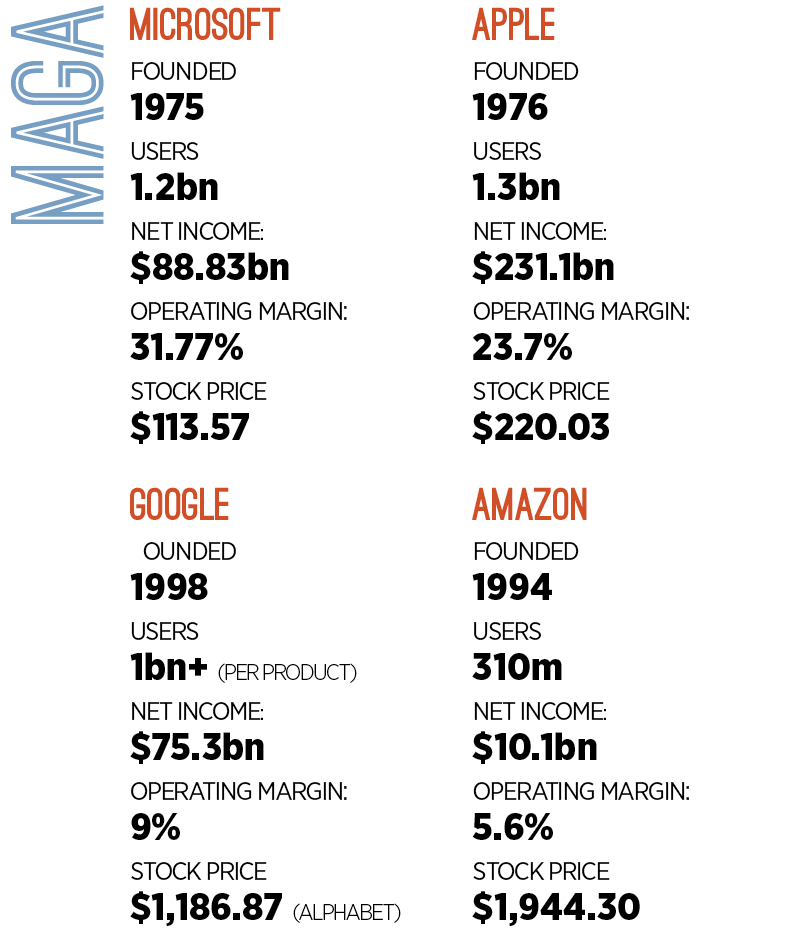

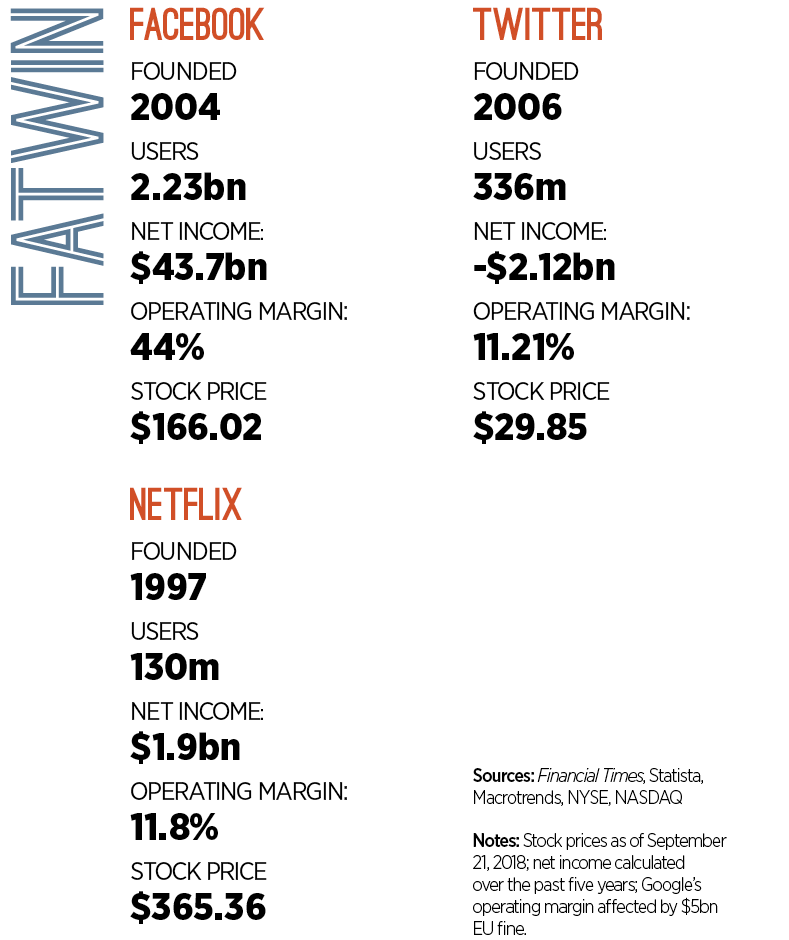

One area in which this conflict is manifesting itself is the world of technology. Although the casual consumer in the West may not have heard much about Chinese businesses Baidu, Alibaba or Tencent (BATs), the Silicon Valley heavyweights of Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google (FAANGs) are certainly aware of them.

Often categorised as FAANGs versus BATs, the battle for tech supremacy between the US and China will have ramifications that extend far beyond the businesses that are directly involved. The winner will not simply claim the economic spoils, but the ideological ones, too.

East meets West

If China’s BATs are not household names in western markets, that doesn’t make their business credentials any less impressive: controlling more than 70 percent of the Chinese search engine market, Baidu is the world’s second-biggest search engine; Alibaba is vying with Amazon to be the internet’s largest retailer; and earlier this year, Tencent overtook Facebook to become the world’s most valuable social network.

Like their US counterparts, the BATs grew their respective core offerings of search, e-commerce and social media before branching out into other fields. These are not the only major technology firms to emerge from the East, either: the likes of JD.com, Xiaomi and Didi Chuxing all have multibillion-dollar valuations.

While China’s tech giants lack the brand recognition of long-established firms like IBM or Intel (in the West, at least), they are catching them up in terms of value. Given both Tencent and Alibaba have recorded year-on-year profit growth of more than 50 percent in 2018 – Baidu could only manage a comparatively modest 45 percent – it surely won’t be long until they overtake them.

Mark Greeven, a Chinese-speaking Dutch professor of innovation based in China for over a decade and the author of Business Ecosystems in China: Alibaba and Competing Baidu, Tencent, Xiaomi and LeEco, noted how the success of Chinese firms reflects a multitude of factors: “Besides the fact that companies like Baidu, Tencent and Alibaba were first movers in China, [benefitted from] fairly good macroeconomic conditions and faced an eager consumer market, the main factor [behind their success] is their business models.

“Instead of building a traditional corporation, they developed business ecosystems. This boundaryless business approach leverages a new way of organising and exploits the benefits of both strategic planning and entrepreneurial decision-making. Core to this business approach is putting the user at the centre and building a deeply embedded business ecosystem around the user’s needs.”

The competition between tech firms in the US and China is underpinned by a broader economic rivalry. In 2000, China’s GDP per capita was just three percent of the US’, while purchasing power parity was eight percent. By 2017, these metrics had reached 14 percent and 28 percent respectively. China’s labour productivity is also rising relative to the US, and it is already a more important export market for eight of the world’s 20 largest economies.

Driven by a rapidly expanding middle class, China’s tech firms are making the most of the country’s economic rise. China’s population – more than four times as large as the US’ – gives domestic firms a huge market to target before they even need to consider international expansion. Chinese citizens are also extremely tech-savvy – they spend more money online than Americans, and have rapidly embraced mobile payments and smart-home devices.

The protectionist bent of the Chinese Government has also proved helpful. By making it difficult for US tech firms to prosper in the country, China has created the perfect incubation space for its homegrown businesses. It is hard to argue that the likes of Baidu and Tencent haven’t benefitted from Chinese censorship of Google and Facebook.

While the BATs continue to thrive, challenges are mounting for the FAANGs. Regulation is already cutting margins in some markets and threatens to do so in others. Profitability, though strong for Facebook, Apple and Google, and growing for Amazon, remains a distant dream for Netflix. Despite the fact US tech firms are still leading the way globally, they are perhaps looking over their shoulders with a little more concern of late.

A tale of two governments

The tech juggernauts of the US and China may both have similar growth aims, but their respective markets are vastly different. Beijing’s interventionist approach to business governance contrasts sharply with the light-touch regulation that Silicon Valley firms are used to. This presents both advantages and disadvantages.

China’s market growth (as a proportion of US growth)

GDP per capita

3%

2000

14%

2017

Purchasing power parity

8%

2000

28%

2017

The benefits for Chinese firms have been significant. Facebook has never had a huge presence in China, where attitudes to social media are significantly different to those in the West. However, until midway through 2009, Mark Zuckerberg’s company boasted approximately one million monthly active Chinese users – a fraction of Facebook’s global total, but something to work from at least.

Surprisingly, this was as good as it ever got for the social network in the country. After being accused of fuelling discontent during the 2009 Ürümqi riots in the Xinjiang region, Facebook was blocked in mainland China, resulting in user figures plummeting by almost 50 percent in the space of a month.

Facebook-owned WhatsApp has faced its own bans in the country, and Google’s search services have been blocked since 2010. Netflix has also struggled to gain a foothold, and only recently managed the feat by signing a licensing deal with Baidu’s own video streaming service, iQiyi.

China is fiercely protective of its online territory in a way that governments in the West are not. If Beijing is not able to censor the content published by foreign businesses, then the firms will simply not be permitted to operate in the country. The relatively open digital landscape in the US provides scant preparation for life behind China’s Great Firewall.

Crucially, it should be pointed out that many large tech firms from the West, including the likes of Siemens, Philips and General Electric, have successfully entered China – it is only those in the internet space that are facing major challenges. Greeven believes that while government restrictions on foreign players remain a barrier to entry, it is not the sole reason for their struggles.

“Another main reason for the failure of US internet firms to succeed in China is a lack of market understanding,” Greeven told The New Economy. “A handful of interesting cases demonstrate this. For instance, Amazon operates in China but does not do as well as local competitors (such as JD.com) because [it does] not understand the market well enough. Google was only blocked in 2010 after entering the market about a decade earlier. The fact is that Baidu had already bested Google [in Chinese searches] in the early years… [It is] the dominant search language in China. Uber also underestimated the local competitor Didi Chuxing and misunderstood the local ‘game’.”

If the actions of Xi’s government have created challenges for US firms, they have generated friction with Chinese firms as well. In August, regulators ordered Tencent to remove its Monster Hunter: World video game from its PC store, WeGame, just days after it was released.

Although Tencent officially reported that the removal was due to “a large number of complaints”, the Financial Times quoted an unnamed WeGame executive who blamed bureaucratic infighting at the regulatory body. Regardless of the motives, the impact on Tencent has been clear and immediate: shares in the company fell by 2.5 percent following the ban.

Ironically, a lack of regulation in the West has also proved damaging for the FAANGs. In recent times, Facebook has been accused of harvesting data without permission, »

spreading misinformation and inciting violence. Amazon, Apple and many others have been accused of tax avoidance while their owners have become some of the wealthiest individuals in the world.

A failure to rein in these companies has led to a backlash, damaging share prices – albeit temporarily in most cases. Evidently, both the BATs and the FAANGs are yet to achieve the perfect relationship with their respective governments.

Neutral ground

Talk of an economic battle between the US and China is rife, and yet many of the chief combatants are largely being kept apart. The US’ online companies are refused access to Chinese markets, while firms like Tencent and Alibaba have little to no US presence.

The inexorable progress of globalisation means the BATs and FAANGs are likely to come into closer contact with one another in the coming years

This hasn’t resulted in the contest being put on hold: instead, the US and China are vying for supremacy in emerging markets where the opportunities for growth are enormous. In Greeven’s words: “It is a global battleground and the Chinese tech firms are aware of that.”

South-East Asia, where e-commerce is expanding at a compound annual growth rate of 29.2 percent, will be a key battleground, as will Africa. Facebook has already launched a Free Basics app in 27 African states to provide free access to several online services, and is competing with Google to boost digital connectivity on the continent. Similarly, many Alibaba services have been made available, and the company also supports African entrepreneurship through its eFounders Fellowship.

Achieving dominance in emerging markets may be a shared aim, but the BATs and FAANGs often differ in their approaches. US firms are happy to start from the ground up, leveraging their brand recognition to set up international subsidiaries: Amazon has committed $5bn to ensure its Indian branch, launched in 2013, is a success. Facebook, Google and Netflix, meanwhile, operate their services in Indonesia, Singapore and elsewhere under their well-known monikers.

Conversely, China’s digital heavyweights often focus on making investments in smaller local players instead. Although Alibaba is challenging Amazon for a slice of the South-East Asian e-commerce market, it is not doing so out in the open. Instead, Alibaba has chosen to compete through Singapore-based firm Lazada, a company it bought a majority stake in two years ago. Similarly, Tencent has made investments in several Indian start-ups across numerous sectors, ranging from healthcare to telecoms.

In terms of international expansion, however, the FAANGs definitely have a head start. More than half of the earnings recorded by Alphabet – Google’s parent company – come from outside the US. Facebook and Netflix also boast international revenues at around the 50 percent mark. Amazon’s numbers are lower – about a third of its revenue comes from overseas – but in some markets outside the US, it has had a presence for two decades.

Chinese firms are trying their best to catch up. According to CB Insights, Tencent and Alibaba – alongside the latter’s investment branch, Ant Financial Group – have provided financial backing to 43 percent of all Asian unicorns. By 2025, Alibaba aims to have half of its sales revenue coming from abroad.

If China’s ambitious tech firms are to achieve their expansionist aims, they’ll have to overcome some negative perceptions first. The close relationship between the private and public spheres in China has caused anxieties in other countries, which have used national security concerns to curtail the growth of Chinese technology firms. Australia recently banned Huawei from providing a 5G network in the country, while the US Government has increasingly scrutinised Chinese investments into domestic tech firms.

Baseless or not, the perception that Chinese firms are a vehicle for Beijing to steal intellectual property and sensitive information could make it difficult for the BATs to expand abroad, particularly in countries with a long democratic tradition. It may be true that Facebook and Google are hardly squeaky clean in this regard, but nations with close ties to the West may feel it’s better to trade with the devil they know than the devil they don’t.

World domination

The US technology giants may be in front for now, but China’s BATs are happy to play the waiting game. Knowing that AI is set to become a cornerstone of the global economy in the years to come, the BATs are aggressively investing in R&D in this space: Baidu Venture Capital raised $317m for an AI-focused fund earlier this year; Alibaba is testing autonomous vehicle software; and one of Tencent’s company slogans is ‘AI in all’.

BATs year-on-year profit growth (2018)

45%

Baidu

50%+

Alibaba

50%+

Tencent

Government support for China’s homegrown firms could give them the edge, but it could just as likely prove counterproductive. If, as has been suggested, Beijing wants a direct stake in its most successful digital companies, the dynamism commonly associated with its private sector could soon be stifled.

On the other hand, US firms have their own issues to overcome if they are to dominate the AI sphere. Facebook’s AI efforts are already struggling to correctly identify fake news and hate speech, while all western tech firms are fighting a privacy backlash from the public. Chinese firms won’t struggle to get hold of the data they need to fuel their AI algorithms; US ones might.

According to Greeven, the rise of Alibaba and other Chinese businesses needn’t be seen as a threat to their US counterparts – it’s not a “zero-sum game”. However, even if the digital economy needn’t be adversarial, it is inherently political. In today’s climate of trade wars and tariffs, the ambitions of the BATs are often viewed with suspicion in the West.

The inexorable progress of globalisation means the BATs and FAANGs are likely to come into closer contact with one another in the coming years – and not only in emerging markets. Google is rumoured to be eyeing a return to China and, in July, Facebook announced its intention – ultimately refused by state regulators – to open a start-up incubator in the city of Hangzhou. The BATs, meanwhile, all have a presence in Silicon Valley. It would be to everyone’s benefit if proximity led to collaboration,

but a clash seems more likely.

If Chinese firms can become world leaders in the technologies of tomorrow, then no number of trade barriers can prevent them from spreading into new markets – even those in the US. As Vladimir Putin said in 2017, whoever becomes the leader in AI “will become the ruler of the world”. The battle between the BATs and the FAANGs isn’t really about becoming the world’s most popular search engine, online retailer or social network – it’s much more important than that.