Making the best of the web: Customer analysis

Many web users are wary of the details they transmit while browsing. As Marion Koob writes, online behavioural tracking is the future of customer analytics

The CEO of Mozilla had a revelation. Gary Kovacs realised web pages he visited allowed other websites to ‘track’ information about his browsing. In other words, the pages he viewed transmitted data about his online behaviour to third parties. Speaking at TED in February 2012, he said: “Not even two bites into breakfast and there are already nearly 25 sites that are tracking me. I have navigated to a total of four.” He recounts that his nine-year-old daughter fared no better while visiting children’s websites, and as a parent, he worried: “Imagine in the physical world, if someone followed our children around with a camera and a notebook, and recorded their every movement?”

Thankfully, this comparison is misleading. Trackers do not collect ‘personally identifiable information,’ or anything that may reveal the user’s identity. In this sense, to compare trackers to the behaviour of a real life stalker might be considered a pessimistic exaggeration. What is most curious is that, in contrast, while users are typically concerned by the number of third parties collecting data, as well as the content of the data itself, knowing about trackers does not change online behaviour.

A study by the University of Salisbury, Maryland confirmed this. Despite the discovery that most consumers dislike being tracked and are conscious that information is collected in order to generate targeted advertising, many do not let it change their performance. Save for the zealous few who will download blocking programs, informed consumers continue to browse as before. This may be because users suffer few tangible costs as a result of behavioural tracking, aside from the unpleasant awareness.

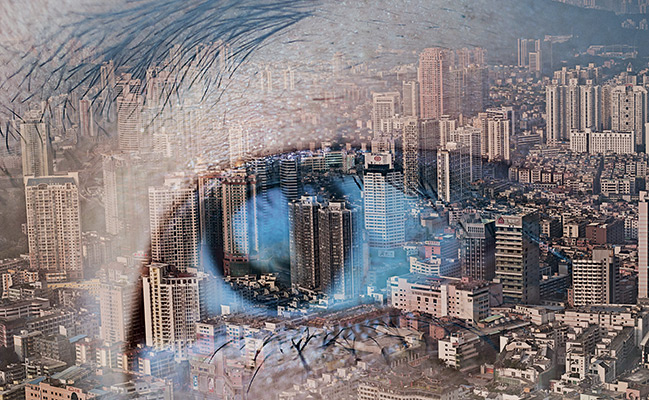

This has not stopped Mozilla from developing an add-on called Collusion, which shows which third parties collect information resulting from a visit to a given website. Collusion displays browsing as a spider web of connections between trackers and your sites of interest. After a few hours of internet usage, the size of the diagram exponentially grows into a daunting network of trackers and the tracked. Yet, many online whizzes complain that Collusion is not as sensitive in detecting these as similar programs, such as Better Privacy, No Script, Ghostery or Tracker Block, which in addition offer the option of blocking third parties from retrieving information. Mozilla aims to provide a new version of Collusion that will also have a blocking function.

Despite Kovacs’s alarmist tone, the official Collusion web page does recognise that “not all tracking is bad. Many services rely on user data to provide relevant content and enhance your online experience”. The firm’s aim is to compile data willingly submitted by Collusion users and make the information available to the greater public for the benefit of research.

Raising awareness is the mission of many privacy advocacy groups, as well as industry regulators, such as the Network Advertising Initiative (NAI), which unites 90 firms that use behavioural tracking under a self-imposed standard. In addition to providing information and enforcing its rules, the NAI also offers users of its member websites an opt-out tool. Big industry names such as Google, Microsoft, Yahoo!, AddThis and AppNexus are members. Meanwhile, organisations such as Privacy International raise awareness and lobby governments for greater protection of personal information (although while visiting their website, an internet user will be tracked by Piwik Analytics).

Evidon, a US-based data and privacy firm, which produces the add-on Ghostery, is a leading firm in providing transparency tools to ensure that firms are complying with their privacy policies. Their business caters both to firms and consumers. For instance, their tools allow firms to provide greater information about advertisements or information collected by third parties, while others notify the user as to whether implicit or explicit consent is required for a cookie to be installed on their computer.

In terms of legal regulation, European governments have taken a conservative stance on the issue. An EU e-Privacy directive was passed in 2009, requiring users give their consent before having third-party cookies installed on their machines. This law came into effect in May 2012 in the UK, requiring that websites inform and request consent of their users for the presence of cookies. Neelie Kroes, European Commissioner for Digital Agenda, recently requested the World Wide Web Consortium, the organisation responsible for setting rules of use for the internet, to set as a default a ‘Do Not Track’ standard.

Meanwhile, Viviane Reading, the European Commissioner for Justice, Fundamental Rights and Citizenship, condemned a March 2012 revision of Google’s privacy policy, which enabled the corporation to combine information compiled across all its services, including Search, YouTube, Picasa and email in order to generate more specific profiles for individual users.

Preference referral

Whereas behavioural tracking has changed little in the consumer’s relationship towards internet use, it has altered the content that target markets interact with online. Targeting means consumers are shown only links and recommendations tailored to individual preferences. This potentially limits consumers’ awareness of competitor products and encloses us in what author and activist Eli Pariser describes as a ‘Filter Bubble’.

Consumers are placed in a self-sustaining cycle, reducing the size of the individual’s marketplace. The links they click are used to narrow down our preferences, further enclosing us within predetermined characteristics. Facebook, for instance, uses this to determine which posts feature most prominently on a user’s newsfeed.

As a result, the internet’s potential as a means to openly share a wide range of information is limited. In this sense, Pariser argues, the power of gate-keeping has moved from publication editors to algorithms.

For example, Google collects characteristics from the user’s machine to refine search results according to what it believes to be his or her preferences. Jeremy Keeshing, writer of blog thekeesh.com, developed a script that shows Facebook’s ‘EdgeRank’: the ranking of your friends based on your interaction with them.

Organisations seeking to take advantage of behavioural tracking need to be careful not just with how they attain the information, but how they use it, bearing in mind the savvy nature of today’s consumer. When it was discovered that users of Orbitz.com who owned PCs were targeted for ads for cheaper hotels than those using Macs, there was an outcry of ‘digital discrimination’.

It is possible for users to alter their online profile. Looking at the ads preferences section on Google allows one not only to view which classifications one has been attributed by behavioural tracking, but also to edit and delete these characteristics.

Tracking organisations install third party cookies, which save a small amount of data on the user’s web browser. At the user’s next visit, the browsing history can be retrieved through the cookie. Web beacons, images of a few pixels or features embedded in a webpage, report site traffic, unique visitor counts, and personalisation, such as your favoured volume on a YouTube video. Locally shared objects or flash cookies not only store more complex data, but are much more difficult to opt out of. Browser fingerprinting identifies a series of settings, which makes a computer uniquely identifiable. This method has also provoked protests from privacy advocates, as it is also impossible to avoid.

Trackers combine various sources of information into one identity if the user crosses over to other websites within the tracker’s network. Profiles are assigned to a specific anonymous identity, churning out consumer categories or aggregate data.

Shortly after the release of Collusion, the Guardian called for readers to submit the data from the add-on after a day’s worth of browsing. With this data, they measured the 10 biggest trackers. Unsurprisingly, Facebook, Twitter and Yahoo! feature on the list, as well as two divisions of Google: DoubleClick and Google Analytics. The former creates income from publishers and advertisers: the latter allows website publishers to gather more information about their web use. Facebook also uses tracking for its social plugins, but not for targeted advertising, for which it uses the information its members freely provide. In addition, as soon as a non-member lands on a Facebook page, it tracks their browsing progress. If that non-member ultimately signs up to the network, Facebook gets a sense of what persuaded them to do so.

Also among the top 10 are giants specialised in tracking and targeted advertising, such as Quantcast, Comscore, AppNexus and Nielsen. These firms buy the right to access information from websites with heavy traffic and sell the information on to firms looking to advertise. Ghostery indicates that the New York Times allows access to the following list: Audience Science, BrightCove, Chartbeat, Check M8, DoubleClick, Dynamic Logic, Facebook Connect, Google AdSense, NetRatings SiteCensus, Score Card Research Beacon and Web Trends.

Tracking solves a major problem in both consumer and organisational markets; it saves time. It’s a proven hit; Google made 96 percent of its revenue from tracking techniques in 2011.

In many ways, Gary Kovacs is right to raise concerns about the transmission of information: users have the right to know their behavioural traits are being analysed for commercial gain. Many websites offer an opt out, but with warnings that many of their functions may no longer work as a result. Governments also need to make sure trackers toe the line with regards to Personally Identifiable Information and privacy advocates have pressurised governments to do so. Between July and December 2011, the US government made 6,321 requests for data to Google, which complied in 93 percent of cases and led to 12,243 user accounts being specified. To its credit, all these results are published on Google’s transparency website.

Advocates have argued tracking behavioural information online has little difference from supermarket loyalty cards and other forms of market research. Perhaps the continual increase in reliance on the internet makes users more protective of their information: as does the uncontrollable nature of the net itself. Those wishing to utilise information extracted from online research should, in turn, be conscious of society’s level of acceptability before putting a brand in peril.

What do trackers track?

– How often a user returns to a website

– The path of a user’s journey from one website to the next

– The time of a user’s visit and the title of the visited webpage

– The user’s IP address (from which their location can be inferred)

– The user’s browser and its language

– Whether the user clicked on a given ad