In bed with Big Brother: Apple and IBM form strategic alliance

Strategic alliances may be trumpeted as offering companies huge opportunities, but they’re sometimes just the last throw of the dice by firms in need of fresh ideas

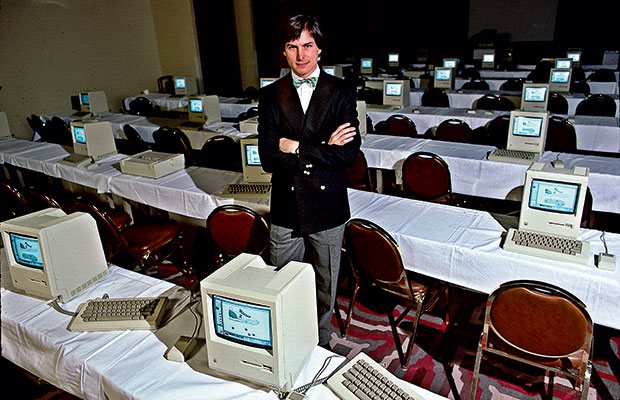

Steve Jobs in 1984. The young Apple exec was outspoken in his contempt for then-rival IBM

When two companies decide to come together as part of a strategic alliance, they usually trumpet the deal as the exciting start to a happy union. However, such alliances can often be the result of two desperate companies being flung together in a last ditch effort to compete with their respective rivals.

Forming a partnership that benefits both parties is often seen as a cost-effective way of expanding a business into new areas without creating too much of a financial burden by building a new division of a company. However, while sharing expertise across two companies can obviously have its benefits, it also comes with a large number of problems that can cause difficulties for both businesses.

The news that two of the world’s leading technology companies – Apple and IBM – would be entering into an exclusive strategic partnership caused shock among many within the industry. The deal, which will see the firms collaborate on developing a leading role in the enterprise software arena, raised eyebrows among those who remember the less than respectful relationship the two have had in the past.

Difficult history

Apple and IBM’s history goes back a long way, and has not exactly been peaceful. Fraught with tension, Apple’s relationship with IBM in the early days of the 1980s was often that of a brash young upstart doing battle with the established, more corporate rival. Such was the competition between the two companies that Apple founder Steve Jobs was photographed making a somewhat uncomplimentary gesture outside IBM’s offices, while his firm ran an advert during the 1984 Super Bowl that showed IBM as ‘Big Brother’ in an Orwellian future: the message was that Apple was the fresh and friendly alternative. Jobs was even more explicit in a keynote speech: “It is now 1984. It appears IBM wants it all. Apple is perceived to be the only hope to offer IBM a run for its money. Dealers initially welcoming IBM with open arms now fear an IBM-dominated and controlled future. They are increasingly turning back to Apple as the only force that can ensure their future freedom. IBM wants it all and is aiming its guns on its last obstacle to industry control: Apple. Will Big Blue dominate the entire computer industry? The entire information age? Was George Orwell right about 1984?”

The partners in an alliance are seen as a bunch of losers clinging to each other with the hope that there’s safety in numbers

The two companies took very different approaches to the computer market, with Apple’s closed-off system standing in stark contrast to the more open platform IBM offered. While Microsoft ultimately succeeded in overtaking both to become the dominant personal computer platform, Apple’s ‘walled-garden’ approach saw it fall far behind IBM.

IBM’s move towards enterprise computing and Apple’s focus on consumer products has meant the two operate in very different spheres nowadays. They have, however, tried to partner up before – most notably in the early 1990s when they formed the AIM Alliance with Motorola. All three firms were struggling against the dominance of Microsoft, and the alliance was created to develop leading processors and software for both the consumer and enterprise markets. Unfortunately, most of their attempts to crack these markets had failed by the end of the decade, and the AIM Alliance fell apart.

Hands in each other’s pockets

Apple has struggled to break into the corporate market, with most offices around the world preferring to use Microsoft’s Windows platform over Apple’s OS X. In the personal computing market, Microsoft reportedly outsells Apple at a rate of 19 to one. In the mobile market, Apple iOS platforms had to play catch up with RIM’s BlackBerry smartphone, which was favoured by corporate clients. While BlackBerry’s market share has dropped at an alarming rate in recent years, many big companies still hold strong reservations about putting Apple’s services at the centre of their IT operations. Long held as a consumer- and media-focused company, Apple’s business services have been seen as lacking in comparison to those offered by its rivals.

The exclusive nature of the Apple-IBM deal gives the former a huge opportunity to tap into the latter’s large number of corporate customers and get them to switch to its iOS platform. Apple plans to launch a “new class” of more than 100 enterprise solutions as part of the deal, many of which may come in the form of native iOS applications. Another feature will be optimised IBM cloud services tailored specifically for iOS, which will allow IT departments to manage devices, security and analytics in a more efficient manner. Apple will also offer an exclusive form of its AppleCare insurance product to IBM customers.

Tim Cook, Apple’s CEO, said in a statement accompanying the deal that it represented a “radical step for enterprise”. He added: “iPhone and iPad are the best mobile devices in the world and have transformed the way people work, with over 98 percent of the Fortune 500 and over 92 percent of the Global 500 using iOS devices in their business today.” In particular, Apple wants to harness IBM’s strong analytics business for the benefit of corporate clients. Expressing an admiration for IBM Jobs would scarce have countenanced, Cook said: “For the first time ever we’re putting IBM’s renowned big data analytics at iOS users’ fingertips, which opens up a large market opportunity for Apple. This is a radical step for enterprise and something that only Apple and IBM can deliver.”

The man at the top of IBM was also keen to trumpet the significance of the deal. Ginni Rometty, Big Blue’s Chairman, President and CEO, added in the same statement that the deal will transform the way people work: “Mobility – combined with the phenomena of data and cloud – is transforming business and our industry in historic ways, allowing people to re-imagine work, industries and professions.

“This alliance with Apple will build on our momentum in bringing these innovations to our clients globally, and leverages IBM’s leadership in analytics, cloud, software and services. We are delighted to be teaming with Apple, whose innovations have transformed our lives in ways we take for granted, but can’t imagine living without. Our alliance will bring the same kind of transformation to the way people work, industries operate and companies perform.”

Mutual benefits

Some in the industry sounded a note of caution over the deal. Jean-Louis Gassée was an executive at Apple during its early years in the 1980s, and knows a considerable amount about the two firms’ previously factitious relationship. He wrote: “Alliances generally don’t work because there’s no one really in charge, no one has the power to mete out reward and punishment, to say no, to change course. Often, the partners in an alliance are seen as a bunch of losers clinging to each other with the hope that there’s safety in numbers. It’s a crude but, unfortunately, not inaccurate caricature.”

Starbucks placed its coffee outlets inside bookstores, offering shoppers the chance to sit back and read while enjoying an overly milky coffee

However, Gassée believes the Apple and IBM deal will be different: “Another, more immediate, effect, across a wide range of enterprises, will be the corporate permission to use Apple devices. Recall the age-old mantra You Don’t Get Fired For Buying IBM, which later became DEC, then Microsoft, then Sun… and now Apple. Valley gossip has it that IBM issued an edict stating that Macs were to be supported internally within 30 days. Apparently, at some exec meetings, it’s MacBooks all around the conference room table – except for the lonely Excel jockey who needs to pivot tables.”

For all the failed strategic alliances, there have been a number that have worked and helped bolster the businesses of both partners. There are also a few firms that have successfully employed strategic alliances throughout their history to enhance their brands and widen their reach.

Starbucks, the seemingly ubiquitous global purveyor of weak coffee, saw a dramatic transformation in the early 1990s after two decades as a struggling chain restricted to the West Coast of the US. In 1993, it formed a partnership with book retailer Barnes & Noble, placing its coffee outlets inside the bookstores, and offering shoppers the chance to sit back and read while enjoying an overly milky coffee. The success of the partnership led to people spending an increased time in Barnes & Noble, browsing for longer, and buying books they’d had a chance to sit down and try while drinking their coffee. It also gave Starbucks an image boost, by associating the brand with a more sophisticated clientele. Starbucks has since copied the model with many other big chain stores, including PC World in the UK. In 1996, it joined forces with PepsiCo to bottle and sell a Starbucks-branded coffee drink (the Frappuccino) in shops and supermarkets. It has also struck deals with airlines, retail stores and restaurant chains, including United Airlines, Kraft Foods and McDonald’s.

One of the longest standing partnerships between companies operating in different industries is the one between Disney and Hewlett-Packard. The firms have worked together since 1938, when Disney acquired equipment to help create the sound design for its film Fantasia. The two have worked together ever since, with HP currently supplying much of Disney’s IT network.

Even Apple has had a number of strategic alliances – with varying degrees of success. It has offered exclusive deals to telecoms giant AT&T for its iPhone (something that probably favoured that company more than Apple in the end) and entered a partnership with leading e-discovery firm Clearwell Systems in 2010 to bring better analytical services to businesses and law firms through the iPad.

Failed friendships

However, there are plenty of examples of alliances that have failed. In late 2009, German auto giant Volkswagen (VW) announced it was acquiring a substantial stake in Japanese manufacturer Suzuki Motor Corporation. The deal saw VW take 19.9 percent of Suzuki for €1.7bn and sign an agreement to share technologies and global distribution networks. It seemed as though it would help both firms break into each other’s markets, with VW dominant in Europe but struggling to crack Asia. Part of the deal saw VW allow Suzuki to have use of much of its electric and hybrid vehicle technologies, while the Japanese firm offered its German partner its own technologies, as well as access to its lucrative hold of the Indian market.

Sadly, the partnership quickly unravelled in a storm of disagreements and cultural differences. By October 2011, Suzuki claimed VW had breached its contract, particularly in failing to hand over the hybrid technology. A month later, the two companies terminated their agreement to work together, and Suzuki demanded VW return its near 20 percent stake: something the German firm refused to do. The dispute eventually went to an international arbitration court and continues to rumble on. This summer, the London-based court announced it had finished taking witness hearings and will likely make a decision on the case by the end of the year.

US tech giant Cisco Systems has consistently failed in efforts to forge partnerships with other firms. It has attempted in the past to work with both Motorola and Ericsson in an effort to enhance its operations. However, after Google acquired Motorola, the company ceased being a partner of Cisco and became a competitor. Similarly, Cisco’s 2004 alliance with Ericsson to modernise the wireline communications market collapsed after Ericsson made a number of acquisitions that made it a direct competitor with its strategic partner.

As Gassée wrote: “There was a time when strategic alliances were all the rage. In 1993, my friend Denise Caruso published the aptly titled ‘Alliance Fever’, a 14-page litany of more than 500 embraces. The list started at 3DO and ending with Zenith Electronics, neither of which still stands: 3DO went bankrupt in 2003, Zenith was absorbed by LG Electronics. These aren’t isolated bad endings.”

Whether Apple and IBM’s deal will go the same way is unknown. Certainly Apple needs to do something to challenge the dominance of Microsoft in the corporate market, as well as persuading IT departments it has the strength of service and security that has so far deterred them from fully signing up to the Mac ecosystem. Likewise, IBM will hope that partnering with Apple will allow some of its former rival’s success to rub off, while also giving it access to Apple’s lucrative consumer market.

In order for it to be a success, there need to be clearly defined boundaries as to what the two firms are offering, as well as trust and full disclosure about the enterprise markets they are pursuing. Cook has maintained this will not be a problem, telling CNBC: “It’s landmark. It takes the best of Apple and the best of IBM and puts those together. There’s no overlap, there’s no competition. They’re totally complementary.”