“Socialites” get hacked off with lack of prosecution

William Henry looks at social media infiltration and wonders why it keeps happening, and what can be done

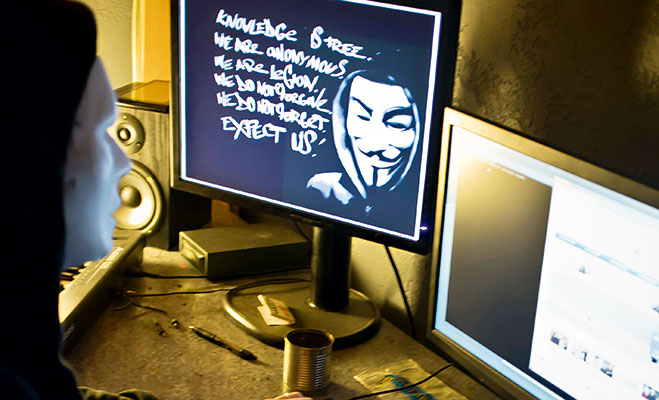

The world is full of hackers, or so it seems. Barely a day goes by without news of a fresh security breach. With so much personal information being uploaded to social databases like Facebook, Twitter, and Google +, a hacking on a personal page is almost, if not akin to a burglary. Except the threat is not a physical one, it’s some enigmatic malevolent marauder who has trespassed in someone’s personal cyber-space, rather than a living room.

In early June, social networking website LinkedIn said some of its members’ accounts were “compromised” after reports that more than six million passwords had been leaked. Hackers posted a file containing users encrypted passwords onto a Russian web forum, making them invalid, forcing people to change their details. The news came as LinkedIn was further forced to update its mobile app after a privacy flaw was uncovered by security researchers.

Facebook continues to remain a main target for hacking and phishing, but even its own engineers are getting involved in the act. When the social media giant went public on NASDAQ and CEO Mark Zuckerberg rang the opening bell, his Facebook page automatically posted a status update: “Mark Zuckerburg listed a company on NASDAQ.” The engineers had used Facebook’s Open Graph API to essentially turn the bell into an integrated application. While the hack was a bit of a publicity stunt, it indicates that it’s very possible to create physical pieces of hardware that trigger Facebook updates, which is slightly unsettling.

With all of today’s technology and complicated code, coupled with all the so-called ‘experts’ who are meant to prevent hackers from getting in, why does it keep happening? Since social media is a fairly new concept, there are going to be weaknesses in the software and infuriatingly, hackers will always try to exploit these. In the past, a hacker would have spent many hours guessing username and password combinations, but now they have access to software, thanks to the clever programmers who built these tools for them. Once they latch onto a server that does not kick them off after five incorrect guesses, the software can guess billions of username and password combinations, and they don’t even need a list of passwords.

As the sophistication of computer hackers developed, they began to come onto the radar of law enforcement. During the 1980s and 1990s, the US and UK passed computer misuse legislation, giving them the means to prosecute. A series of clampdowns followed, culminating in 1990 with Operation Sundevil – a series of raids on hackers with bombastic names like the Legion of Doom, the Masters of Deception and Neon Knights. However, hackers remain undeterred: a current favoured practice is to infiltrate social media accounts by sending out messages filled with spam, containing viruses within links.

The sudden growth in the number of hackers is not necessarily down to schools improving their computing classes or an increased diligence and much flexing of programming prowess on the part of young, IT enthusiasts – more often than not, it is the result of Attack Tool Kits (ATKs) – widely available software designed to exploit website security holes.

Keeping the front door, back door and windows locked by maintaining convoluted passwords and changing them regularly, installing a beefy firewall, and running regular virus checks to ensure nothing unsavoury has been uploaded are normally the most efficient ways to deter hackers. Yet, if they are determined to, they will find a way to get in.