Collection of genetic data leads to privacy concerns

The market for at-home DNA tests is booming. As the companies behind them amass more genetic data, privacy advocates have raised concerns that consumers lack much-needed protection

A DNA test can reveal surprising facts about us – certain genes make us more inclined to have dry earwax, for example, and others make us more likely to sneeze when we see a bright light. Some genes even result in people being more attractive targets for mosquitoes, so if you’ve ever felt personally singled out by the insect during the summer months, it’s not a cruel conspiracy – it’s your DNA.

Innocuous facts like these were what DNA kits were used for finding out when they first became commercially available. However, as the tests have become more sophisticated, the companies behind them have shifted their marketing focus. Users of at-home DNA tests have been known to uncover deep-rooted facts about themselves, from discovering long-lost relatives to learning of their ancestors’ origins and their susceptibility to genetic diseases.

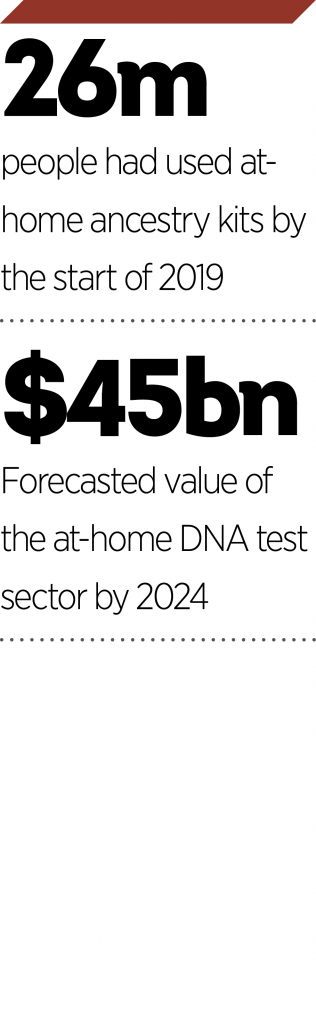

Finding out that you have a pre-existing health condition might not seem like the best idea for a Christmas present, but that hasn’t stopped the test kits from enjoying a surge in popularity. MIT Technology Review estimates that by the start of 2019, more than 26 million people had taken an at-home ancestry test. The market is expected to be worth $45bn by 2024.

Nevertheless, despite the emerging industry’s rampant growth, there have been mounting concerns that its practices could infringe on consumers’ rights. Whenever people fork out $100 to $200 for a DNA test, the hidden cost of that transaction is their personal data – which, from then on, is held in the databases of a private company. Once these companies obtain genetic information, it’s very difficult for users to get it back.

By taking DNA tests at home, many have unwittingly stumbled upon long-kept family secrets. Some have seen their parents go through a bitter divorce after their test revealed they were actually conceived through an affair

Ignorance is bliss

Long before people were able to take DNA tests from the comfort of their own home, psychologists worried about their possible impact on people’s mental health. Ever since the Human Genome Project was started in 1990, many scholars have maintained that DNA tests should be used with caution, on the grounds that understanding one’s own health risks could lead to anxiety or depression.

Conversely, a study by the Hastings Centre found that discovering an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease did not make people more depressed or anxious. And in the event that people discover a particularly urgent health risk – like a mutation of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, which puts individuals at a high risk of developing cancer at a young age – any adverse psychological effects are presumably worth it to obtain this life-saving information.

However, at-home DNA tests could still pose a risk to mental health, in part because they remove medical professionals from the equation. Adrian Mark Thorogood, Academic Associate at the Centre of Genomics and Policy, warned that this is far from best practice for receiving a DNA test result. “Results should be communicated through a medical professional who can interpret the result in the individual’s specific context, and offer a clear description of the test’s limits,” he told The New Economy.

Without a professional’s assistance, users could be left alone to battle with a troubling revelation about their health. There is also a danger that without guidance, some people could misinterpret their test result, placing undue stress on their mental health.

There is another unpleasant discovery that people can make through a DNA test – one they may be even less prepared for. By taking DNA tests at home, many have unwittingly stumbled upon long-kept family secrets. Some have seen their parents go through a bitter divorce after their test revealed they were actually conceived through an affair. Others have discovered they were conceived by rape and that their mother decided to never tell them. What began as a seemingly harmless urge to find out more about their heritage ends in psychological trauma and family breakdown.

Brianne Kirkpatrick, a genetics counsellor, is part of a growing sector of therapy specifically tailored towards helping people come to terms with receiving unexpected DNA results. One can’t help but wonder whether her patients end up wishing they’d never taken the test at all.

“I don’t recall anyone saying they wish they could go back and not learn the truth,” Kirkpatrick said. “But I have had a number of people say to me they wish they had found out their shocking information from a person, rather than a computer.”

While we might think we’d prefer to suffer a DNA leak than a leak of our credit card details, genetic data has its own unique set of complications

The fact that virtually anyone can now find out their real parentage through a simple DNA test has wide-reaching repercussions for the accountability of paternity. Historically, men have always had a much greater ability to conceal their status as a parent, as they don’t have to bear the child. The world of direct-to-consumer DNA testing blows this capacity for anonymity out of the water.

This is particularly problematic when it comes to sperm donation. Anonymity is a key selling point for many potential donors, but now all their future biological offspring has to do is swab the inside of their cheek to completely compromise that anonymity. Research suggests that we could see a drop in donor rates as a result. A 2016 study in the Journal of Law and the Biosciences found that 29 percent of potential donors would actually refuse to donate if their name was put on a registry.

The wave of parental discoveries made through direct-to-consumer DNA tests raises questions about where the responsibility of the seller sits in all this. Most health professionals recommend that individuals seek out genetics counselling once they receive DNA results. Some, like Invitae, offer counselling services but aren’t direct-to-consumer companies. Many of those that are – including 23andMe – do not offer such a service. It could be argued that this shows a certain disregard for the consequences of using their product. Unfortunately, irresponsible decisions like this have tended to characterise the industry’s path to success.

Genetic Wild West

In September 2019, 17 former employees from the Boston-based genetic testing company Orig3n accused the firm of giving consumers inaccurate results. Allegedly, if a customer took the same test twice, their results could be extremely different each time. A former lab technician produced a leaked report to Bloomberg Businessweek that revealed 407 errors like this had

occurred over a period of three months.

Part of Orig3n’s USP was that it offered advice supposedly calculated based on a consumer’s genetic profile. Former employees have cast doubt over the company’s modus operandi by claiming that the advice they gave was in fact routinely lifted from the internet. The advice given ranged from the technically correct but uninspired to the broadly unhelpful – such as telling people to eat more kale – and the utterly bogus, like advising clients to eat more sugar to eliminate stretch marks.

Although Orig3n is a relatively small player in the sector, news of this scam nonetheless illustrates how little protection consumers have in this nascent market. Analysts say we are currently witnessing a ‘Wild West’ period in the consumer genetics space thanks to a lack of regulation, raising concerns over whether we can trust these companies with our genetic data. While we might think we’d prefer to suffer a DNA leak than a leak of our credit card details, genetic data has its own unique set of complications.

“In the United States, if my social security number is stolen, that is difficult, but not impossible, to get frozen, changed, etc,” said Natalie Ram, an associate professor at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law and a specialist in bioethics and criminal justice. “But there’s literally no way to change your genetic code.”

Genetics platforms like 23andMe, AncestryDNA and FamilyTreeDNA are now sitting on a goldmine of very personal data. In 2013, a 23andMe board member told Fast Company that it wanted to become “the Google of personalised healthcare”. If this statement makes anything clear, it’s that the company wasn’t planning on making its millions simply by selling DNA test kits: its mission was always to amass significant amounts of data on its users, which it could then monetise.

There is a wide range of reasons why companies might want to buy genetic data. Perhaps the most benign is medical research, which genetics platforms allow users to opt in or out of. But other companies might use your genetic data to better sell you products or, conversely, deny them to you – for instance, one sector that would see a clear monetary value in obtaining genetic data is insurance. In the US, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 prevents employers and health insurers from using a person’s genetic information when making decisions about hiring, firing or raising rates. However, this does not include life insurance or short or long-term disability insurance.

At first glance, it seems as if there’s a simple solution: if users are concerned about these risks, they should just choose for their data to be kept anonymous. However, choosing this option is not as foolproof as it once was. As long ago as 2009, researchers demonstrated that they could correctly identify between 40 and 60 percent of all participants in supposedly anonymous DNA databases by comparing large sets of that data with public datasets from censuses or voter lists. Since that experiment, DNA databases have grown massively.

“With access to four to five million DNA profiles, upwards of 90 percent of Americans of European descent will be identifiable,” said Ram. “It’s verging on a comprehensive DNA database that no US state or jurisdiction has suggested would be appropriate.”

Shaping the law

With comforting statements like “your privacy is very important to us” (ancestry.co.uk) and “we won’t share your DNA” (familytreedna.com) emblazoned on their websites, some genetics platforms seem to be making privacy their number one priority. In the US, 23andMe and Ancestry are part of the Coalition for Genetic Data Protection, which lobbies for privacy protection in the DNA space. However, while the coalition advocates genetic data privacy in a specific context, it argues for a one-size-fits-all policy concerning all data. By comparison, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation regards genetic information as ‘personal data’, which makes DNA unique from other kinds of data.

There is a fundamental legal problem with boxing genetic data in with all other varieties, including the data that social media websites collect about us. In most cases, what a person does on the internet implicates them alone – genetic data is different. We share our DNA with members of our family, which means that sharing it without their consent can be problematic.

“Even if I can consent to using my DNA to identify me, that should not extend to my ability to consent to using my DNA to identify my relatives,” said Ram. “The reason I think… that’s a really critical distinction is because genetic relatedness is almost always involuntarily foisted upon us. So we don’t choose our parents, we don’t choose how many siblings we have. It’s a product of biology, not a product of choice.”

The legal issues surrounding genetic relatedness were put to the test in 2018 when police discovered the true identity of the Golden State Killer, who terrorised California in the 1970s and 1980s in a homicidal spree. Law enforcement officials were able to convict him only because they had succeeded in connecting the DNA of the suspect with that of a family relative on GEDmatch, a genetic database in the public domain. Across the US and around the world, people celebrated the arrest of a notorious criminal. The only problem was that the means of capturing him was not necessarily legal.

Prior to the case, GEDmatch’s site policy made no explicit reference to the potential use of consumer’s data by law enforcement. However, the company defended itself by saying that users should have assumed it could be put to that use.

“While the database was created for genealogical research, it is important that GEDmatch participants understand the possible uses of their DNA, including identification of relatives that have committed crimes or were victims of crimes,” said GEDmatch operator Curtis Rogers in a statement.

Some genes even result in people being more attractive targets for mosquitoes, so if you’ve ever felt personally singled out by the insect during the summer months, it’s not a cruel conspiracy – it’s your DNA

However, privacy advocates like Ram argue that users’ consent for law enforcement to look at their data should not have been assumed. “At least from a constitutional perspective in the United States, individuals ought to be recognised to have what’s called an expectation of privacy in their genetic data, even if they use one of these services,” she told The New Economy.

After the case, genetics platforms updated their policies to clarify their position on law enforcement’s use of people’s data. Interestingly, they took very different stances. While 23andMe and Ancestry said they would not allow law enforcement to search through their genetic genealogy databases, FamilyTreeDNA updated its policy to say it would give up data to officials, but only in the investigation of violent crimes. Users didn’t know it at the time, but FamilyTreeDNA’s policy update was already too little too late: in January 2019, it was revealed that the company had been secretly working with the FBI for nearly a year to solve serious crimes, without informing its users.

The Golden State Killer case exposed how little protection consumers really had in the direct-to-consumer genetics market. It showed that genetics platforms were capable of suddenly changing or contradicting their own policies and even, in the case of FamilyTreeDNA, betraying the trust of consumers.

Some might argue that this infringement on genetic privacy is simply the price we must pay to catch dangerous criminals. Of course, without the use of a genealogy database, the Golden State Killer may never have been caught. But the fact that genetic data can be harnessed to solve very serious crimes should not justify law enforcement’s unbridled access to such databases. Abuses of power do happen and, in the context of direct-to-consumer DNA tests, they already have: in 2018, for example, Canadian immigration officials compelled a man to take a DNA test and upload his results to FamilyTreeDNA’s website. They then used the website to find and contact some of his relatives in the UK to gather more evidence in order to deport him.

Today’s consumers are continually adjusting to shrinking levels of privacy. From the introduction of video surveillance and the mapping of residential areas on Google Earth to the revelation that Facebook harvests vast amounts of user data, we have seen the public react in the same way again and again: there is an initial public outcry, and then consumers simply adjust to the new level of diminished privacy. Our response to the rise of genetics platforms risks the issue being consigned to the same fate.

It is up to regulators to protect individuals’ right to privacy. While our genetic data may be something of a genie out of the bottle, that should not give the companies that collect it free rein over who sees it and what they choose to do with it.