Behavioural economics may not have all the answers, but it’s close

Neoclassical economics is flawed; it values neatness over reality. Behavioural economics offers a new scientific framework and tools for understanding data

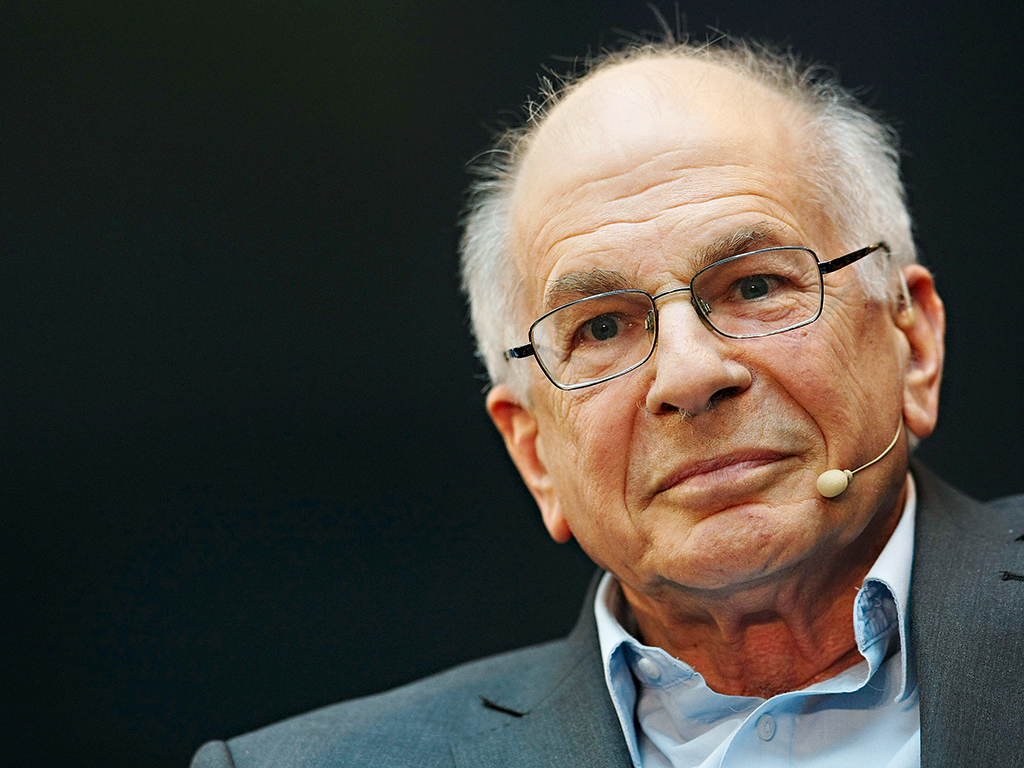

Daniel Kahneman’s insights led to the creation of behavioural economics

In 1955, Daniel Kahneman was a psychologist in the Israeli army, charged with finding out which soldiers would make good officer material. He devised a simple test: divide the men into groups of eight, remove their insignia to hide rank, and tell them to lift a telephone pole over a six-foot wall. This would reveal who were the leaders, who were the followers, and who were the quitters (or thought lifting ridiculously heavy telephone poles over a wall was a waste of time). After each batch, Kahneman and his team would recommend those soldiers they thought had the right stuff for officer school.

Every now and then, Kahneman would get feedback from the school on how his recruits were doing. The news wasn’t all good. It seemed being talented at pole-lifting didn’t translate directly into being good officer material. In fact, according to Kahneman, “there was absolutely no relationship between what we saw and what people saw who examined them for six months in officer training school”.

We put too much faith in our power of judgement, and tend to ignore or downplay information that doesn’t agree

Interestingly, this piece of information did not change Kahneman’s mind about the validity of his technique. “The next day after getting those statistics, we put them there in front of the wall, gave them a telephone pole, and we were just as convinced as ever that we knew what kind of officer they were going to be.”

Kahneman thought he was testing the soldiers – but he turned out to be testing himself. He was clinging to his theories, even when they were in conflict with data. He later coined a name for the phenomenon: “the illusion of validity.” We put too much faith in our power of judgement, and tend to ignore or downplay information that doesn’t agree.

Although it came too late to save the army careers of a number of soldiers, the insight would eventually lead to the creation of a new field of study – behavioural economics – that is now influencing behaviour at the highest level of governments, and reshaping our understanding of economics.

The psychology of stupidity

The irrational behaviour revolution got underway, suitably, in the heady period of the late 1960s, after Kahneman moved to the US and began a long academic collaboration with the psychologist Amos Tversky. They soon found a number of decision-making situations where people tend to act less than rationally. For example, they showed we have an asymmetric attitude towards loss and gain: we fear the former more than we value the latter, and bias our decisions towards loss-avoidance rather than potential gains. Our response to a question also depends on the way it is framed. More people will support an economic policy if the text emphasises the employment rate rather than the corresponding unemployment rate.

Their work did not meet with immediate appreciation. Kahneman relates meeting a well-known American philosopher at a party: after Kahneman started to explain his ideas, the philosopher turned his back, saying, “I am not really interested in the psychology of stupidity.” (One imagines he then tripped and spilled his drink over someone’s shirt.) But they had a better rapport with a young American economist called Richard Thaler, who helped them apply their ideas to economics. Together with other scientists, they built up a picture of human economic behaviour that was complex, and often less than flattering.

Some of our other various foibles and predilections include:

- Compartmentalising: losing a £10 note on the street feels worse than losing the same amount in a stock portfolio, because they are handled in different mental compartments.

- Status quo bias: we prefer to hold onto things rather than switch to an alternative, even if it is better.

- Denial (the illusion of validity): we maintain beliefs even if they are at odds with the evidence.

- Loss aversion: investors avoid selling poorly performing stocks, because they have to face up to the loss.

- Suggestion: we are influenced by the opinions of others. Our tastes and preferences are therefore not fixed.

- Trend following: this fuels bubbles in asset prices, because, when the market is going up, we think it will continue.

- Illusory correlations: we look for patterns in things like stock prices where they don’t exist (they’re talking about you, chart followers!).

- Immediacy effect: one study showed we will pay on average 50 percent more for a dessert at a restaurant when we see it on a dessert cart, than when we choose it from a menu.

Many of these behavioural patterns have been confirmed by the experiments of neuroscientists, who put people in scanners and see which parts of their brains light up when offered the choice between a fully funded pension on retirement, or an ice cream that they can have right there.

Now, to many people, the idea that we hold on to theories long past their best-by date, or squander our future and that of our children in favour of immediate gratification, will not come as a huge surprise. The reason it proved controversial – and we are still talking about it – is because it posed a profound challenge to the traditional theories that make up our rather Victorian economic worldview.

Rational mechanics

Mainstream ‘neoclassical’ economics traces its roots back to the late 19th century, when its Victorian founders decided to put the classical economics of Adam Smith and others onto a sound, mathematical footing. Inspired by Isaac Newton’s ‘rational mechanics’, they attempted to model the exchange economy using equations similar to those in physics – but to do so, they had to make a number of assumptions.

The most basic of these was that people acted to optimise their own utility, i.e. whatever made them happy. As Francis Edgeworth put it in 1881: “The first principle of Economics [sic] is that every agent is actuated only by self-interest.”

People also had a fixed set of preferences. So, if they like cereal for breakfast, they don’t suddenly swap over to eating toast. And people always acted in a completely rational fashion. This would mean, for example, that if a psychologist told you to help carry a telephone pole over a wall for no obvious reason, you as a rational person would either refuse, or pretend to help while actually doing as little as possible. Unless, of course, you had intuited that this was part of an exam, in which case you would loudly order other people around.

As economics developed in the 20th century, concepts such as rationality remained at the heart of the theory

Thus was born the notion of homo economicus, or rational economic man. While these assumptions had obvious flaws, they did allow economists to construct elegant mathematical models of the economy. And as economics developed in the 20th century, concepts such as rationality remained at the heart of the theory.

For example, the Arrow-Debreu theorem famously showed that a market economy would reach a kind of optimal equilibrium – but only if all participants acted rationally to maximise their utility, not just now but also in the future. Since the future is unknown, this means they have to know what is the best course of action for every possible future state of the world – something that implied infinite computational capacity, a kind of hyper-rationality. The Arrow-Debreu model served as the theoretical foundation for General Equilibrium Models, versions of which are used today to determine the effects of policy changes on the economy.

Eugene Fama’s Efficient Market Hypothesis, meanwhile, provided a convenient excuse for why economists were doing such a poor job of predicting the future. It portrayed the market as a swarm of “rational profit maximisers” who drive the price of any security to its “intrinsic value”. It was therefore impossible to beat or out-predict the market because any information would already be priced in. The market was the epitome of rationality. This idea formed the backbone of models used in risk analysis.

The assumptions of neoclassical economists therefore had a dual nature. On the one hand, they were designed to make the economy mathematically tractable. It is obviously easier to model people who are selfish, have fixed preferences, and are completely rational, than it is to model people who are influenced by the opinions of others, change their minds for no reason, and make puzzling and bizarre life choices. On the other hand, they shaped the way we see and model the economy; as a beautifully rational and efficient system.

Adding epicycles

Following the recent crisis, which went completely unpredicted by these models, the assumptions behind economic theory have come under intense scrutiny. As even Alan Greenspan admitted, the belief that markets acted rationally turned out to be wishful thinking.

One response to this challenge – which was fully in line with what one would expect from a study of behavioural economics – was to deny there was a problem, cling to the illusion of validity, maintain the status quo, and thus avoid loss. The other response was to try and somehow incorporate the findings from behavioural economics into mainstream theory. However, this has proved difficult because the two are fundamentally inconsistent.

The immediacy effect makes us more likely to buy something when it is immediately accessible, and is considered one of the main reasons people fail to plan properly for their retirement

The main attraction of the neoclassical theory was not so much its ability to generate outstandingly accurate predictions about the economy (it doesn’t) but the fact that it provides a kind of ‘theory of everything’ for the economy. Scientists prefer simple theories with the maximum explanatory power. But while it is possible to model a rational person using elegant equations, everything becomes much more complicated when you include irrationality.

Consider, for example, the immediacy effect, which makes us more likely to buy something when it is immediately accessible, and is considered one of the main reasons people fail to plan properly for their retirement. One way to handle this mathematically is through a technique known as ‘hyperbolic discounting’. But when you try to account for the fact that people are different from one another, but influence each other through social and other connections, the entire structure of mainstream economics breaks down.

These tweaks and adjustments to the model are the modern equivalent of the epicycles that ancient astronomers added to their geocentric models of the cosmos, in order to make them better fit reality. They cannot disguise the fact that the fundamental assumptions of the model are wrong. The universe does not rotate around the Earth, and the economy does not rotate around homo economicus.

The illusion of validity

It is possible to make more realistic models that take into account behavioural effects through newer techniques such as agent-based modelling, network theory and so on. However these methods lack the mathematical elegance of neoclassical theory, and fail to be a theory of everything because they depend on so many local and temporary factors. Applications of behavioural economics therefore tend to take the form of pragmatic suggestions for improving things such as government procedures.

An early endorser was the UK Government, which employed Thaler as a consultant when it set up a group of economists and psychologists called the Behavioural Insights Team (or ‘nudge unit’ as it is known, after the title of Thaler’s 2008 book Nudge). One of their ideas was to send out court fines by text message rather than by mail. This electronic nudge improved compliance rates from one in 20, to one in three. Researchers have also shown participation rates in pension plans can be significantly increased just by making that choice the default option, so employees must opt out if they wish not to take part.

Nudging sounds a lot like manipulation, and some have voiced ethical concerns about the state employing such tricks to control behaviour. As Thaler notes, though: “There are people nudging you every day, and it’s not the government. If you go into the supermarket, somebody’s figured out the most profitable way of having you walk through the store.”

This is certainly true, but it also points to the fact that behavioural economics does look a lot like a highly scientific version of marketing. Marketers and advertisers have probably learned as much, through sheer trial and error, about controlling our responses through the power of suggestion and immediacy – or for that matter by sending unsolicited text messages – as any nudge unit. Parents have been devising devious techniques to ‘nudge’ their children for even longer.

Behavioural economics goes beyond something like marketing by providing both a formal scientific framework, and new tools for data analysis. In the long run, though, perhaps its greatest contribution to human knowledge will be a negative one. For too long, economics has been labouring under an illusion of validity, confidently prescribing policies such as deregulation of the financial sector (oops!) or harsh austerity (the economic equivalent of lifting telephone poles over a wall) even when empirical evidence says they are not working, and justifying them with abstract mathematical models that only economists can understand. By pointing out the fundamental inconsistencies of mainstream economics, behavioural economics may hasten the development of true alternatives, which may even include a dose of humility.

That would be no small achievement. After all, as Charles Darwin observed: “To kill an error is as good a service as, and sometimes even better than, the establishing of a new truth or fact.” Behavioural economics may have found its perfect application – to change the behaviour of economists.