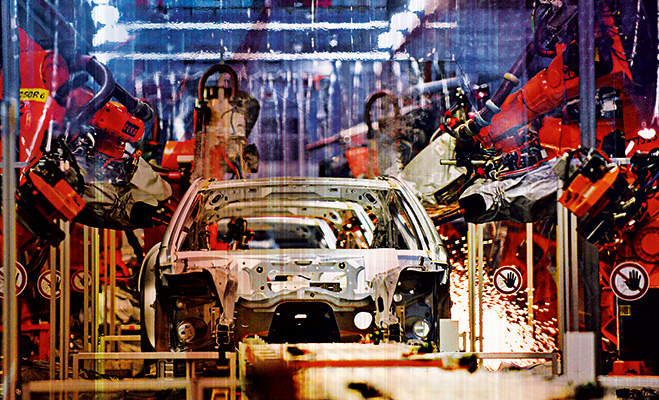

Manufacturing acknowledges the rise of the machines

Financial constraints and innovations are convincing companies to look at automating production. It isn’t all bad news for human workers

Technological innovation has led to many industries developing more efficient forms of production, but at the unfortunate cost of shedding employees. Those managing major corporations are understandably eager to reduce the costs of manufacturing: a great deal of which come from paying wages to huge numbers of employees.

The impact of automating such processes on local economies can often be hugely damaging. Job losses in many countries, particularly at a time of economic difficulty, are deeply unpopular. As the working environment changes and technology advances, many employees in traditional industrial jobs are finding themselves out-skilled and redundant.

However, allowing one machine to replace large numbers of human workers can, if done correctly, bring benefits not only to the private corporations, but also to the economic environment in which those corporations operate. Software algorithms can solve some simplistic actions and robots are able to carry out repetitive factory processes.

Some argue that the replaced workers will be able to focus on more creative-based work. Freeing up people to do less boring tasks could lead to a fundamental improvement in business innovation. Automation could also lead to improvements in time-management and worker efficiency.

Automatic future

It is likely the use of robots in the manufacturing industry will steadily increase. Some people believe this to be a natural progression of technology that will enable human workers to fulfil more suitable tasks. CEO of Adept Technology John Dulchinos said: “If you look out far enough, machines are going to win. The human body… was not designed to be a factory machine. It was designed to be a thinking machine.”

Although automating work processes will likely lead to a significant increase in productivity, while also improving quality control, some companies have increased their workforces in order to cater for the increased output. There are also companies, notably car manufacturer Toyota, which have sought to combine automation with an increase in human workers.

Innovation Matrix specialises in distributing Japanese robotic technology across the US. According to CEO Eimei Onaga, the use of robots in the workplace is only going to increase. He said: “The cost of machinery is going down, while labour costs are rising. Soon, robots could even replace low-cost workers at small firms, greatly boosting productivity.”

A number of other benefits have led many companies to look into implementing automated systems throughout their factories: from a reduction in waste to a lowering of costs and better use of energy. The use of machines to carry out manufacturing processes has been enthusiastically embraced in Asia, and in particular Japan. The Japanese government invests over $10m each year in developing key robotic technologies.

Amazon has 18 ‘fulfilment centres’ in the US, 20 in Europe and 10 in Asia, allowing it to spread its network of operations across much of the globe, increasing delivery and sourcing speed, and turning the company into the world’s largest online retailer

Europe has also been looking to adopt automation systems, with German and Swedish firms leading the way. Germany has 43 percent of Europe’s robot workforce, while exporting a great deal more than the rest of the continent.

Although the US lags somewhat behind the rest of the world in automating industries, there has been a stark increase in recent years. Millions of jobs over the course of a few decades have been outsourced from the US to cheaper markets. The number of domestic manufacturing jobs has decreased by 30 percent since 1990. Manufacturing output, however, has only dropped one percent in that time, reflecting a lesser reliance on human workers and an increase in automation.

Foxconn

Foxconn is one of the world’s most talked about manufacturing companies. It has come in for considerable criticism for the conditions in which its workers build the latest tech gadgets. Some of the most recognisable tech brands in the world use Foxconn to build their devices, including Apple, Hewlett-Packard, Sony and Dell.

A spate of suicides relating to highly controversial working conditions in their Chinese factories, coupled with the soaring demand for the smartphones and tablets that they make, has led Foxconn to begin looking at ways in which it can automate its manufacturing. In 2011, Foxconn President Terry Gou announced plans to replace one million workers with robots by 2014.

Updating the press on the company’s plans in November 2012, Gou spoke of the first batch of robots – called the ‘Foxbots’ – which were already operational in one factory. He added that by the end of 2012, there would be another 20,000 installed. Little is known about the Foxbots as the company has designed them in-house.

Foxconn has around 1.2 million employees. Implementing further automation is likely to dramatically reduce that figure, while potentially improving the cramped conditions in which the remainder work. Although each robot is reported to have cost Foxconn almost $25,000 – more than three times the salary of an average employee at the firm – labour costs in China are steadily rising.

The long-term attractiveness of employing robots to do much of the work is obvious.

Salaries at Foxconn’s Chinese factories have jumped between 30 and 40 percent in the past year, and were expected to grow by another 20-30 percent by this year.

Many firms in Chinese industry are recognising the benefits of automation. They will be looking with interest at how Foxconn’s plans pan out. Vice-President of the China Machinery Industry Federation, Zhang Xiaoya, said: “Industrial robots can help Chinese enterprises save costs on company management, food, accommodation, insurance and social benefits for employees. It can also strengthen their competitiveness in technology innovation and product design.”

Amazon

Many firms that have emerged since the advent of the internet have been unburdened by the constraints that large workforces place on companies. Amazon is a particular pioneer of automation. The company recently expanded on its plans for automating its services. In March 2012, it acquired robotic warehouse operations company Kiva Systems for $775m.

Kiva has created a number of robot systems that make warehouse management considerably quicker than with just human workers. Kiva’s technology has been used by a number of other companies, including Gap, Stapels and Crate & Barrel. Amazon executive Dave Clark said: “Amazon has long used automation in its fulfilment centres, and Kiva’s technology is another way to improve productivity by bringing the products directly to employees to pick, pack and stow.”

The idea of bringing an automation company into the Amazon fold makes sense, according to observers. Analyst Scott Tilghman said: “This is a way to improve efficiency. Given the scale of Amazon’s operations, it makes sense to have this capability in-house.” It makes sense for an online retailer that stores a great deal of products in warehouses to use automation as much as possible, as speed in delivery is paramount to their service.

Amazon has been steadily increasing its number of warehouses around the world. Having its own advanced automation systems in place will keep down labour costs in different regions. Amazon has 18 ‘fulfilment centres’ in the US, 20 in Europe and 10 in Asia, allowing it to spread its network of operations across much of the globe, increasing delivery and sourcing speed, and turning the company into the world’s largest online retailer.

Canon

While some companies look to find a halfway point in the way they balance the combination of automation and human workforces, others seem eager to fully embrace an automated production process. Japanese camera maker Canon recently announced plans to move towards a fully automated system over the course of the next few years.

The company hopes that some of its camera factories will be entirely automated by 2015, but insists that the human workers being replaced will simply be moved into other areas to work. Canon’s spokesman Jun Misumi said: “When machines become more sophisticated, human beings can be transferred to do new kinds of work.”

Although the cost-savings of going fully automated are obviously attractive to firms, some feel there are serious downsides to removing a human workforce. While machines are able to piece together components and move products much faster than their human counterparts, they do not yet offer the innovation and flexibility provided by a traditional worker.

If you look out far enough, machines are going to win

Professor Akihito Sano of the Nagoya Institute of Technology thinks the industry is not ready to be run entirely by automated systems. He said: “Human beings are needed to come up with innovations on how to use robots. Going to a no-man operation at that level is still the world of science fiction.” In short, someone has to tell the robots what to do.

Japan has by far the greatest proportion of industrial robots compared to manufacturing workers. Figures from 2008 show that for every 10,000 manufacturing workers there were 295 robots. The closest country behind Japan was Singapore with 169, followed by South Korea with 164. Not all Japanese firms are so enamoured with automation though, and some are looking at ways of balancing a traditional workforce with a mechanical one.

Toyota

Japan’s pioneering automaker Toyota is a company that has innovated in many areas of production over the years, and was one of the first to introduce a form of automation to the production of its cars. In recent years, however, the company has begun implementing a system that combines the efficiency benefits of automated manufacturing with the flexibility of a human workforce.

Someone has to tell the robots what to do

Known as ‘autonomation’, the process allows the company to prevent defective products and overproduction, and to adapt to any problems that arise. The University of Michigan’s Professor Jeffrey K Liker, an expert on the firm, said: “Toyota has generally backed off when it put in too much automation and added back more people. And its latest processes have even more people than a couple of decades ago.”

Adaptability is key when it comes to Toyota’s strategy, according to Professor Liker, with human workers capable of doing a number of different tasks. He said: “for many jobs [Toyota] believes that people are more adaptable, it can add or subtract people easily and move them around.”

Too much automation led Toyota to discover it had created a “fixed cost” and therefore reduced its own flexibility.

Professor Liker said: “Toyota’s new global engine line has less technology than existing lines and its new assembly lines also have less technology. By reducing both overheads and technology, it is more flexible to adapt to changes in the environment. I believe Toyota has more of a balance between technology and people. And where it has technology, people in the work groups in the area are still at the centre as they maintain and have responsibility for the equipment.

“What I have observed is that when management treats people like cogs in a machine, workers will accept it as long as they are satisfied with pay and job conditions, but they will not contribute their ideas to improve the process. The last thing [Toyota] wants are people acting like robots that just do what they are told.”